di Clovis WHITFIELD

Agostino fu parte essenziale del team Carracci e non è quindi realistico diminuirne il ruolo, nonostante verso di lui -che era il fratello più anziano e più istruito- ci fosse la rivalità di Annibale il quale ambiva alla fama completa con i lavori della Galleria Farnese.

Il racconto di Mancini e quello di Agucchi sono preziosi perché sono registrazioni di persone che conoscevano entrambi, invece il racconto di Baglione (1642) sembra essere scolorito dal passare del tempo e dalla estraneità con i protagonisti, mentre Bellori appartiene ad una generazione successiva e Malvasia ha un punto di vista interamente bolognese riguardo alle loro carriere. Il nocciolo del racconto di Agucchi è che i due fratelli intrapresero il lavoro – implicando tutte le decorazioni di Palazzo Farnese e alcuni dipinti ad olio – in armonia, finché i disaccordi comportarono che l’anziano se ne andò quando ancora la maggior parte della Galleria era incompiuta. L’aneddoto del racconto di Cavedone sui primi disegni del Trionfo di Bacco inviati da Annibale allo studio dei Carracci a Bologna, per mostrare ciò che poteva ottenere senza la direzione di suo fratello, non è stato preso in considerazione. Questo mostra che egli in primo luogo pensava alla decorazione della Galleria in continuazione con il tipo di progetto del fregio che aveva avuto successo in Palazzo Magnani, e la successiva assegnazione del Trionfo di Bacco al centro della volta, con le due scene di Agostino da una parte, può essere attribuito alla revisione dell’idea originaria, ed infatti Annibale aveva trascorso tre anni a Roma senza risolvere il progetto e non intraprendendone alcun altro importante. Alcune ipotesi di base devono essere chiarite: egli non era necessariamente un esperto che aveva tutta l’iconografia e la quadratura a portata di mano, e padroneggiare la mitologia classica era qualcosa che non aveva mostrato in precedenza, comprensibilmente aveva bisogno di una spinta, e anche se Federico Zuccari stava rivendicando il diritto alla pittura di essere classificata tra le arti liberali in una campagna che avrebbe finalmente incontrato qualche successo, esiste un certo numero di prove che suggeriscono che Annibale si considerava un pittore, un artigiano la cui manualità era la sua pretesa di fama, e l’essere stato relegato dal Cardinale Farnese ad alloggiare nei soffitti di Palazzo Farnese, nei quartieri di servizio, è il riconoscimento di un umile status che la sua fama successiva non può cancellare.

Come Caravaggio, Annibale non sembra nemmeno appartenere all’Accademia di San Luca né essere stato un uomo di grande erudizione. Al contrario, la necessità prevalente nel Cinquecento di avere un letterato che traducesse le intenzioni del committente in un linguaggio che l’artista avrebbe capito, s’incontrò in modo singolarmente innovativo in Agostino, ovviamente a proprio agio in entrambi i mondi, in un modo tale che gli appassionati di Gabriele Paleotti, di Melchiorre Zoppio, o perfino di Giovanni Baglione, non avrebbero mai potuto raggiungere. Annibale evidentemente aveva bisogno del coordinamento e della diplomazia di suo fratello, ma quando ciò si sviluppò fino al punto che quest’ultimo giunse a competere per il riconoscimento artistico sul soffitto stesso, ci furono parole amare e l’impazienza che aveva per la sua interferenza venne fuori. In realtà c’era una lunga storia non solo del ruolo guida di Agostino nell’attività, ma anche che i dipinti di Annibale erano considerati necessari da riordinare per essere stati giudicati troppo “disordinati”. C’era un ampio raggio di disaccordo, ma ci fu anche il progetto di ulteriori dipinti, come la ‘Venere dormiente’ adesso a Chantilly, che forniva la base della acrimonia tra i due fratelli e che alla fine portarono alla partenza di Agostino. Annibale ricorreva sempre più spesso a delegare al suo allievo preferito i tocchi di finitura, e doveva essere questo che permise di finire la maggior parte del soffitto, perché si può sostenere che la parte principale fosse completa entro la fine del 1600. Senza sottovalutare l’incredibile capacità che Annibale ha avuto per catturare un nuovo naturalismo e un impianto con l’evocazione dell’espressione, dobbiamo anche riconoscere che la decorazione completa offerta dai Carracci fu una produzione congiunta, in cui i talenti separati di ciascuno dei fratelli (e a Bologna, il loro cugino Ludovico) furono complementari.

I contributi individuali di ciascuno nel fregio di Palazzo Magnani erano indistinguibili, “l’abbiamo fatto tutti noi” amavano dire, e in una certa misura ciascuno potrebbe sostituire l’altro, ognuno poteva fare disegni e preparazioni, potendo anche rifinire gli altri dipinti. Nella nostra preoccupazione di riconoscere il genio dell’artista più identificato con la Galleria Farnese abbiamo tralasciato questa considerazione fondamentale, cioè che si trattasse di un’impresa collettiva e cooperativa che proveniva dai talenti dei due fratelli. Un po’ come una coppia che viene percepita dalla personalità incompleta, senza l’altra metà, abbiamo l’impressione di due persone che erano anche opposte e talvolta completamente in disaccordo, e questo alla fine ha portato ad una completa rottura. E mentre l’impressione dominante riguarda il virtuosismo della pennellata di Annibale per la sua brillantezza, una produzione come questa è stata tanto ricondotta tanto alla progettazione che all’esecuzione, mentre invece egli era in realtà il fratello minore di questa partnership. Che ci fosse gelosia tra di loro è un luogo comune: “Ciò che (Annibale) non poteva sopportare era di dover ascoltare tutti dire costantemente che egli era stato battuto da Agostino anche nella pittura, nella sicurezza del grande fregio e in una giudiziosa e ricca invenzione” come Malvasia ricorda. Nei tempi moderni la soluzione di chi abbia scritto il programma per la Galleria ha generato una continua confusione; che sia stata veramente una produzione congiunta, con un fratello che fornisce lo script e l’altro che traduce in pittura è una soluzione molto più probabile che non che fosse uno sconosciuto l’autore letterario che forniva i testi. Però possiamo vedere chi ha messo a punto le storie classiche e ha reso eccitanti i dipinti. Non c’era bisogno di una chiave per la mitologia e le allegorie che erano implicite, poiché il loro autore era presente sul posto e pronto a rispondere ai quesiti quando questi nascevano, avendo già usato testi come le Metamorfosi di Ovidio per insegnare a giovani artisti a Bologna l’invenzione.

I titoli latini che accompagnano le scene di Palazzo Fava diventano meno lunghi e letterari a Palazzo Magnani, e ancor più fittizi a Palazzo Farnese, ma sono il risultato di un apprendimento che Annibale non possiede. Non doveva essere un ‘libretto’ a Roma ma non poteva essere fatto senza l’erudizione di cui Agostino era dotato e il suo carattere spiega l’interpretazione umoristica delle fonti classiche che vediamo in tutte le narrazioni. Ma se fece un programma, il pensiero retrostante si interruppe per la lite arrivata all’apice quando la pittura del soffitto era completa per meno della metà, e, mentre alcune invenzioni erano evidentemente alternative messe in uso dopo che Agostino era partito, il completamento delle pareti realizzato anni dopo non poteva continuare con la stessa ispirazione, perciò tenendo conto della discontinuità dell’invenzione che è sempre stata notata nella decorazione finita. Ciò significa che dovremmo guardare ai disegni per la Galleria, come mai prima, per suggerimenti di iconografia inusuale, per disegni alternativi non adottati e per le idiosincrasie grafiche attribuibili ad Agostino. Ci sono parecchie citazioni di quello che era un patto tra loro che privilegiasse la pennellata di Annibale e allo stesso tempo era noto che non dovesse sempre fare disegni preparatori, perciò possiamo forse cominciare a discernere la divisione solitamente armoniosa del lavoro tra loro. Può essere possibile riconoscere alcuni dei suggerimenti di Agostino per la struttura della Galleria e altri disegni relativi agli affreschi, talvolta scambiati per i pensieri iniziali di Annibale per i vari soggetti a causa delle diverse soluzioni figurative che infine raggiunse. Nessuno degli studi moderni sui disegni ha definito pienamente le loro differenze, e poiché la difettosa conoscenza ebbe inizio anche durante la sua vita e continua senza sosta per sfruttare a fini commerciali la grande fama che i Carracci hanno raggiunto, è estremamente difficile distinguere tra i loro stili. La maggior parte delle informazioni biografiche che abbiamo proviene da una generazione successiva, contaminata dalla ottimistica idea di commercializzare quanto vi fosse di muovibile e vendibile. L’opinione prevalente che Annibale fu in qualche modo responsabile di tutta l’impresa è manifestamente esagerata, e il tenore delle conoscenze, delle suggestioni intellettuali e del gioioso godimento dell’antichità classica e della moderna sessualità ha più a che fare con la personalità del fratello. La differenza nei loro ruoli è in realtà evidente, e mentre apprezziamo giustamente la straordinaria versatilità che l’opera di Annibale dimostra, agli occhi del contemporaneo committente la necessità di direzione era ancora molto più significativa; e non si trattava della solita allegoria cristiana. È più ragionevole suggerire che suo fratello non fu solo responsabile per i dettagli decorativi, ma fosse anche l’architetto dell’intero complesso, l’inventore del contrappunto delle narrazioni e dell’alternanza di materiali fittizi e l’ intellettuale protagonista della narrazione che scaturì dal dibattito intellettuale che aveva con il committente e la sua corte. Deve essere Agostino che ha reso accessibili e intellegibili i miti classici, traducendo in un’antologia visiva la narrazione asciutta che i suoi amici antiquari avevano assimilato, e aggiungendovi la spezia irresistibile del sesso. Egli era in una posizione unica nel mediare tra la competenza antiquaria di Fulvio Orsini, la portata letteraria della poesia di Michelangelo e Tasso e quella di tanti altri autori e la gamma di stili artistici con cui si era familiarizzato durante la sua carriera come incisore e riproduttore. Sarebbe stato il Cicerone che era in grado di spiegare al pubblico romano la natura della scuola veneziana di pittura di cui la Curia si rese conto dopo l’acquisizione da parte di Clemente VIII di Ferrara nel 1598. Certamente quello che conosciamo della sua capacità con cariatidi e con figure di sostegno, spesso in grisaille piuttosto che a colori, coincide con il ruolo che sembra aver assunto nella progettazione del complesso da Palazzo Fava in poi. La sua lunga concentrazione sui media grafici, disegni e incisioni, è stata spesso interpretata come una mancanza di volontà nel competere con il virtuosismo di suo fratello riguardo al mezzo pittorico, ma egli assunse gradualmente più responsabilità fino a quando non potè finalmente contribuire in concorrenza attiva con lui. La supervisione che aveva sul progetto significava che Annibale aveva meno bisogno di fare studi preparatori, tanto che Agucchi disse che lavorava senza nessuno

E’ Mancini che chiarisce che Agostino era venuto a Roma “per condur la galleria di Farnese con il fratello” e questo, si può arguire, significava dirigere il progetto con lui. “Condurre” fu quello che Albani fece per la serie di lunette a Palazzo Aldobrandini e per la decorazione della cappella Herrera in S. Giacomo degli Spagnoli ed è una gestione che spesso viene intrapresa da pittori che non eseguono in realtà scene di grande narrazione, come Agostino Tassi nella Sala delle Muse nel padiglione di Scipione Borghese al Palazzo di Montecavallo o Pietro Paolo Bonzi presso Villa Chigi a Castelfusano. Essi avevano il compito di coordinare il piano globale, di definire le principali divisioni e di decidere quali decorazioni interne, grottesche ed elementi paesaggistici avrebbero dovuto essere inseriti. Questo era dopo tutto ciò per cui erano reputati i pittori bolognesi, progettando quadrature e pianificando in generale schemi di decorazione che incorporassero la scultura fittizia e l’architettura come scenario per scene narrative, così come la prospettiva al loro interno, i pannelli paesaggistici e le grottesche.

L’asma di Agostino e il suo sovrappeso ci fanno immaginare che egli trovasse veramente difficile lavorare ad affresco, ma la sua competenza non era l’unica caratteristica che lo rendeva così importante per la pianificazione del lavoro, egli era anche molto più ricercato da committenti e cortigiani e poteva comunicare con loro. La sua comprensione della storia classica e della mitologia era già stata la base delle conoscenze per le decorazioni, che la famiglia aveva intrapreso a Bologna. Il ruolo del direttore attribuito ad Agostino infatti implicava la designazione di Annibale e dei suoi compagni come pittori nel Palazzo Farnese. Agostino è certo arrivato a Roma dopo che ebbe inizio il progetto della Galleria, perché Malvasia in una delle note associate alla Felsina Pittrice riferisce che Annibale aveva inviato da Roma i disegni del Trionfo di Bacco a Ludovico a Bologna, in modo che il cugino potesse vedere come stava operando senza il consiglio e l’aiuto di Agostino, perché sospettava che il mondo non gli avrebbe dato tutto il merito di ciò che raggiungeva. La nota è quella che Malvasia ha scoperto dalle conversazioni con il principale assistente di Ludovico, Giacomo Cavedone, ma che non sembra poi aver utilizzato nella stessa Felsina, né è stata considerata nel contesto della rivalità tra i fratelli. Nato nel 1577, Giacomo aveva incontrato per la prima volta Annibale nel 1589 quando aveva dodici anni e si unì alla scuola di Carracci nel 1591, e sembra essere stato ben considerato da loro, per come si esaltava nei baccanali (baccieggiava). In questo affascinante aneddoto, che è stato in gran parte ignorato, ricordava che Annibale temeva che la gente pensasse che il suo lavoro a Roma sarebbe stato considerato il risultato della direzione e dell’aiuto di suo fratello – direzione ed appoggio. E non lo voleva a Palazzo Farnese, anche se Agostino si era offerto di lavorare seguendo esclusivamente i suoi cartoni e di essere in sostanza il suo servitore. Giù a Roma da solo voleva sbalordire il fratello o quanto meno mostrare cosa potesse ottenere senza il suo aiuto. Da come appare, Annibale aveva inviato il disegno, in tre sezioni (‘tre fogli reali dissegnati di penna grossa ed ombreggiato dilapis nero’) a Ludovico a Bologna, in altre parole al cugino piuttosto che a suo fratello, perché aveva paura che la gente pensasse che egli non avrebbe potuto farlo e che sarebbe stato visto come risultato dell’invenzione di Agostino. I disegni erano in penna inchiostro e matita nera (spesso descritta oggi come “gesso nero” ma spesso carbone). L’opera impressionò Ludovico e lo copiò (da Cavedone) prima di trasmetterlo ad Agostino a Parma – come se fosse stato direttamente dal fratello – perché voleva sorprenderlo o almeno mostrargli quello che Annibale poteva fare senza di lui. Questo sembra vero, perché i primi disegni del soffitto Farnese sono nel carattere di un fregio – con il Trionfo di Bacco suddiviso in tre episodi distinti – dominato dal disegno delle pareti piuttosto che dalla volta stessa, in continuazione con quella che era stata una soluzione molto felice a Palazzo Magnani, dove il soffitto è piatto con travi e la decorazione dipinta in cima alle pareti. Purtroppo non sono sopravvissuti nemmeno i disegni che Annibale ha inviato a suo fratello, né la copia di Cavedone di essi (che apparentemente possedeva Malvasia), né le copie di Sebastiano Brunetti cui Malvasia si riferisce. Un disegno che riproduce la descrizione (e può essere una di queste versioni piuttosto che l’originale di Annibale) è il grande foglio dell’Albertina di una Processione Bacchica, con molto rilievo di bianco, generalmente considerato un disegno iniziale per il Trionfo di Bacco che non venne adottato.

La storia dà peso all’idea che Annibale fosse in qualche modo dipendente o considerato come se si affidasse alla direzione di Agostino e ciò suggerisce infatti che l’erudizione senza dubbio era stata utile nell’attività familiare per guidare il fratello minore almeno nella scelta di soggetto e contenuto delle immagini che dipingeva, mentre quest’ultimo evidentemente risentiva di questa supervisione del suo lavoro. L’aneddoto rafforza pertanto l’impressione del tipo di sforzo collaborativo che avevano comportato le precedenti decorazioni dei Carracci e, anche se non abbiamo ancora capito la cronologia di questo episodio, e nemmeno della Galleria stessa, è chiaro che la mitologia delle tante scene si basava su conoscenze che non erano nell’ambito di Annibale, ma che erano certamente parte della reputazione di Carracci come attività familiare. Sembra possibile che Annibale non fosse effettivamente in grado di gestire i grandi progetti che era stato chiamato a completare e avesse bisogno di un fratello – il dotto fratello che gli dirigeva il lavoro e dimezzava la fatica – non solo per fornire l’iconografia, ma anche per pianificare il lavoro quotidiano. E seppure i disegni iniziali, descritti da Cavedone, fossero per uno scopo radicalmente diverso, con il Trionfo di Bacco sulla parete piuttosto che al centro della volta, Agostino doveva aver avuto una parte importante nell’eventuale riordino, quando assicurò le due scene da entrambi i lati del pannello centrale, che per lungo tempo sarebbero le uniche parti per cui venne ricordato. Una di loro ha sotto la data 1598, quindi in quella fase molte caratteristiche progettuali del soffitto dovevano essere in uno stato abbastanza avanzato.

Molti tentativi sono stati fatti per circoscrivere la partecipazione di Agostino ai lavori del soffitto perchè arrivò a Roma solo dopo una commissione per un ritratto a Parma del 22 ottobre 1597 e un’altra simile ancora a Parma nel luglio del 1599, che avrebbe limitato il suo lavoro alla Galleria in quel periodo. La lunghezza della presenza di Agostino a Roma non è certa, ma Malvasia dice che avrebbe meritato la metà se non tutto il merito per la Galleria “sariasi attribuito almeno la metà, se non tutta l’onore della Galeria Farnesiana, Già che tutta Roma applaudiva tanto … ” (Felsina Pittrice, 1841, p. 403). Mancini, che conosceva entrambi i loro problemi di salute, ha scritto che la loro rivalità consisteva nel fatto che Annibale voleva per se stesso la gloria della realizzazione, aggiungendo una nota ulteriore – tutta la gloria-, ma ha dato anche un’idea vivida del profondissimo sapere di suo fratello, come un uomo di ‘singularissimo giuditio’. Agucchi, che è tanto vicino quanto deve esserlo un testimone del corso degli eventi, dice che essi iniziarono in armonia “come havesser da toccar ad amendue insieme, senza veruna distinzione” (D. Mahon, Studies in Seicento Art and Theory, 1947 , Pp. 245/55), ma in seguito ai disaccordi promossi da qualcuno che godeva nel vederli l’uno contro l’altro, Agostino lasciò quando la maggior parte della Galleria era ancora da completare e tornò a Bologna e poi a Parma, ma non fino al matrimonio Aldobrandini / Farnese (7 maggio 1600).

L’aneddoto sui disegni di Annibale inviati da Roma è importante perché rivela quale fosse il ruolo percepito di Agostino nella produzione all’interno dell’attività dei Carracci, di cui il fratello minore risentiva e costantemente sminuiva. Il ruolo di Agostino nella vera pittura di Palazzo Farnese fu limitato, perché non solo (qui abbiamo le parole di Agucchi) riconosceva che suo fratello poteva dipingere meglio, ma anche perchè la sua presenza a Roma era evidentemente in una condizione di secondo piano. Come le parole di Mancini e Agucchi, i ricordi di Cavedone, trasmessi a Malvasia, sono importanti perché sono voci di testimoni oculari di eventi che in seguito sarebbero stati soggetti ad ogni interpretazione di persone che al momento non erano presenti.

Il contatto del Duca Ranuccio con i Carracci ebbe luogo evidentemente attraverso Agostino, all’inizio come incisore già nel 1591; era lui realisticamente il punto di riferimento della famiglia per l’assunzione di un potente patronato. In termini di cronologia, Odoardo Farnese, che aveva pianificato già dal 1593 di portare i Carracci a Roma a dipingere nel suo palazzo, scrisse da Roma il 21 febbraio 1595 al fratello (a Parma) per dirgli che aveva deciso di avere i ‘pittori Carracci ‘ per dipingere la Sala Grande del palazzo con le imprese del padre il primo Duca Alessandro, ed essi già qualche mese prima erano venuti a Roma per una visita esplorativa. Aveva bisogno del libro (che aveva lasciato insieme agli effetti del Conte Masi) con disegni della campagna nelle Fiandre affinché i pittori iniziassero. I Carracci avevano fatto varie decorazioni a Bologna, e Malvasia riferisce (I, 295) che Ludovico doveva dirigere il lavoro, portando con sé Annibale (e disse che aveva una lettera del Duca in tal senso).

La decorazione del Gran Salone che festeggia le prodezze di Alessandro nelle Fiandre non è avvenuta perché non c’era nessun testo; allo stesso modo, il Camerino e la Galleria Farnese non procedevano a causa dell’assenza dell’iconografia; l’archeologo Fulvio Orsini non era in grado di fornire il progetto necessario per i pittori. Malvasia racconta che Agostino seguì Annibale a Roma: “V’andò dico, e poco dopo vi andò Agostino” (I, p. 295), e i problemi che i disegni di Annibale suggerivano comportavano che Agostino finalmente lasciasse Parma e si unisse a suo fratello a Roma. C’è sempre stata grande lode per tutto il pensiero e la direzione per cui il fratello maggiore era famoso: l’ “elefante” in quella stanza è infatti Agostino.

La collaborazione, evidentemente, fu al meglio fin quando veniva moderata dal cugino dei due fratelli, Ludovico, e fin quando il talento di Agostino era assorbito dai tanti altri lavori nella riproduzione delle incisioni che prendeva la maggior parte del suo tempo nel 1580. Ma egli aveva piacere per la gloria che derivava dai cicli di affreschi a Bologna e partecipava sempre più alla loro ideazione, soprattutto, a quanto sembra, nella pianificazione dell’intero complesso interno, con un particolare entusiasmo per le cariatidi e altri motivi di inquadrature in grisaille per i dipinti di narrazione, che comunque divennero dominanti come la ditta Carracci divenne più sicura. Malvasia contrapponeva la diligenza di Agostino all’impazienza di Annibale, e c’era da tempo un problema per il modo impaziente e poco pulito di quest’ultimo, perché le prime pale d’altare avevano spesso suscitato critiche per una certa loro scioltezza di mano. Era sempre stato necessario correggere la pennellata più istintiva e frizzante del fratello minore, che non si vedeva come una finitura accettabile, e Annibale aveva evidentemente accettato questa “correzione”; Ludovico aveva apparentemente risistemato il lavoro negli affreschi di Palazzo Fava. Sia o no che vogliamo considerare questo come un difetto, però Annibale (che era notoriamente una persona con un carattere a terra) aveva bisogno anche di un responsabile perché trovava difficile trattare con i clienti, mentre Agostino era colto e capace di conversare con classe (Malvasia, I 265, 327/8). Da un punto di vista personale, Agostino evidentemente amava il fratello svisceratissimamente, come riferisce Mancini, ma questo appare come un affetto protettivo che si alternava con l’impazienza che confinava con l’intolleranza (dal punto di vista di Annibale) per una personalità che era proprio l’opposto della sua. Siamo abituati a ricordare quanto fosse occupato Annibale a Roma dal vivo resoconto di Bonconte nel mese di agosto del 1599, quando Agostino era apparentemente lontano, ma è anche vero che prima dell’arrivo di Agostino nel 1597 o all’inizio del 1598 era accaduto molto poco e il cardinale Farnese poteva essere stato molto insoddisfatto della produttività del team Carracci che aveva assunto. Nei quasi tre anni che Annibale fu a Roma da solo, dall’autunno del 1595, non era stato fatto nulla per eseguire la più importante decorazione apparentemente prevista nel Salone di Palazzo Farnese e il Camerino non era ancora iniziato (era ancora in corso il cambio di secolo); è ragionevole supporre che la Galleria stessa sia stata iniziata solo dopo l’arrivo di Agostino e fu allora che il lavoro andava davvero. C’è quasi il mistero su quello che Annibale fosse a Roma, come negli anni oscuri di Caravaggio dopo la sua ultima apparizione in Lombardia nel 1592 e la sua prima occupazione presso il siciliano Lorenzo Carli nell’inverno del 1595/96. Cosa ha rappresentato la sua arte quando è arrivato a Palazzo Farnese?

Aveva portato con sé la Sacra Famiglia con Santa Caterina (Napoli, Capodimonte) fatta dieci anni prima e dipinto il Cristo e la Cananea per la cappella di Palazzo Farnese che conserva un carattere più ludovichiano, forse dovuto alla familiarità di quest’ultimo con la pittura dello stesso soggetto di Correggio. Sembra un quadro pensato a Bologna ma fatto a Roma, quasi come se Ludovico avesse fornito il disegno alla sua partenza da Bologna. E anche se ciò contrasta con l’idea dell’originalità di Annibale, ricordiamo che Ludovico, come direttore dei Carracci, aveva fornito ad Annibale i disegni prima, con le Pietà di Reggio e Parma, dove Malvasia ricorda come il più anziano dei Carracci fosse ‘il più copioso e feroce In invenzione ‘, e che il lavoro di Annibale necessitasse spesso di una revisione (I, p. 345). Sebbene egli fosse presumibilmente sempre a disegnare e a fare volontariamente schizzi per quelli attorno a lui, nulla di sua mano fu visto in pubblico fino a quando la Santa Margarita venne posta sulla pala d’altare della sua cappella in Santa Caterina dei Funari nel 1600. Questa era in realtà solo una copia di una parte di una precedente pala d’altare in Bologna, cui era stato coinvolto Gabriele Bombasi e il committente (che si era trasferito a Roma) era evidentemente nostalgico di questo tipo di pittura.

La figura riprende la santa Caterina nella pala d’altare (Parigi, Louvre) che Annibale aveva realizzato otto anni prima per la Cattedrale di Reggio Emilia e fu Lucio Massari che la fece a Bologna e, se venne ritoccata da Annibale dopo che arrivò a Roma, non era certamente una nuova creazione. Era comunque un soggetto del tutto conveniente per un cortigiano Farnese al tempo in cui Margherita Aldobrandini era stata indicata per essere la sposa Farnese. Fu probabilmente in questo momento che Odoardo Farnese maturò l’idea di avere Annibale per ridipingere la cupola del Gesù, senza dubbio nell’emulazione della cupola di Correggio a Parma; nel 1599 sponsorizza la costruzione della Casa delle Professe al Gesù e aveva un appartamento appena oltre la cupola stessa. Bombasi, che era stato tutore di Odoardo dopo un lungo patrocinio di Ottavio Farnese, era evidentemente nostalgico per il carattere “veneziano” dell’opera di Annibale a Bologna, e per i Correggi e Tiziani di cui aveva avuto lui stesso copia di copie. Queste copie furono lasciate a Odoardo alla morte di Bombasi nel novembre del 1602 (molti cortigiani esprimevano la loro lealtà con questo tipo di lasciti) e la loro scomparsa fu senza dubbio l’occasione che Boschini descrisse quando il Cardinale produsse un gruppo di dipinti veneziani che dovevano essere di Correggio , Tiziano e Parmigianino – solo per essere rivelato come opera di Annibale. Il tenore correggesco del gusto di Bombasi è illustrato dalla pittura che Annibale fece per lui dell’arcangelo Gabriele circondato da Angeli, ora a Chantilly, e come cortigiano vicino al Cardinale potrebbe essere stato l’ispiratore dell’idea di ridipingere la cupola del Gesù, uno dei grandi progetti che era previsto per Annibale dopo il completamento della Galleria. Ma che non si realizzò, come molto di quello che Odoardo progettò con il suo pittore, e ci restano solo alcune immagini che l’artista ha fatto quando visse a Palazzo Farnese. La paralisi di entrambe le facoltà di direzione e di inventiva di Annibale sia prima dell’arrivo di Agostino a Roma, sia dopo la sua partenza nel 1600, si può leggere come testimonianza dell’importante ruolo che poi quest’ultimo giocò in tutte le decorazioni Farnese. Perché la Galleria non è un assemblaggio casuale degli Amori degli Dei, ma un’accurata scelta di mitologia riportata in vita, corrispondente a ciò che Sallustio diceva del mito, che è qualcosa che non è mai stato, ma è sempre. La preparazione letteraria Agostino e il suo rapporto con gli intellettuali del tempo, combinati con la sua superlativa esperienza degli altri lavori, dimostrata nelle sue incisioni, lo hanno reso un ingranaggio essenziale nel business dei Carracci e l’architetto della sua trasformazione. Annibale, al contrario, era un individuo intuitivo, che aveva un’educazione limitata e più di una volta dichiarò la sua impazienza per la pedanteria di suo fratello e dei cortigiani che portava a discutere mentre dipingeva. Non dovremmo supporre che queste visite non fossero senza effetto, che l’umile pittore al lavoro sul ponteggio potesse respingere i loro commenti e proseguire indipendentemente. Suo fratello era impegnativo e come Mancini dice ‘di singularissimo giudizio che, qualsivoglia minimo errore {d’arte}, subito lo riconosceva, e il fratello, che amava sviceratissimamente, stando a veder operare, diceva qualche cosa, mal volentier sentito da Anniballe , O che non fusse vera o che non volesse questa superiorità ‘. La grande erudizione che tutte le fonti attestano non sarebbe stata dissipata in mero ornamento e decorazione, anche se questa può essere la manifestazione più evidente dei suoi disegni. E con l’esperienza degli studi associati alla Tazza Farnese, dove Agostino è così preoccupato per la decorazione di contorno, dovremmo davvero cercare disegni dove ci siano cornici e motivi per lo spartimento della decorazione, la sfida della divisione della Volta della Galleria in sezioni. L’esistenza di almeno un disegno di Agostino per Eros e gli Anteros, i Cupidi degli angoli della volta, sul verso dello studio della Tazza di Chicago, dimostra come fosse coinvolto in questa importante caratteristica iconografica che per Bellori era la chiave per l’intero impianto della Galleria.

Ci sarebbero ancora alcuni dipinti in cui l’autosufficienza di Annibale brilla ancora, ma sono per lo più opere da stanza, come il Domine, Quo Vadis, che Pietro Aldobrandini acquisì quando visitò e vide il soffitto completato nel 1601, il San Giovanni Battista realizzato probabilmente nello stesso periodo di tempo per Corradino Orsini (un’opera di evidente luminosità ancora perduta, anche se conosciuta da una incisione e una copia), la Pietà di Napoli, un altro piccolo rame adesso a Vienna dello stesso soggetto, le Tre Marie al Sepolcro nella National Gallery di Londra, un’altra grande redazione del medesimo soggetto ora a San Pietroburgo fatta per Lelio Pasqualini, un antiquario bolognese, che era Canonico a Santa Maria Maggiore a Roma.

Questo e l’Incoronazione della Vergine (Metropolitan Museum, New York) che evidentemente venne garantito da Pietro Aldobrandini, probabilmente durante il momento del ravvicinamento con il Farnese per l’unione delle due famiglie nel 1599/1600, dimostrano il sapore correggesco e veneziano che ci si aspettava da Annibale nel suo soggiorno romano. Alcuni si sono accontentati di reminiscenze, come la Santa Margherita che fornì a Gabriele Bombasi, come detto sopra, e il Cristo e la Donna di Samaria, una versione ridotta della composizione nella Pinacoteca di Brera fatta nel 1593/94, poi realizzata per la Famiglia Oddi di Perugia. Un’altra è la piccola Visione di San Francesco, attualmente a Ottawa, giustamente associata al suo sfondo che assomiglia all’architettura di Palazzo Farnese. Questi collezionisti sono stati fortunati: perfino il più ricco appassionato di pittura bolognese, Vincenzo Giustiniani, che con il fratello, Cardinale Benedetto, ebbe accesso all’eredità con la morte del padre Giovanni Giustiniani (morto il 9 gennaio 1600) non ebbe successo nell’ottenimento per sé di un lavoro del maestro, anche se continuava a impiegare i pittori bolognesi (Albani, Domenichino, Viola) per decorare la sua villa di campagna. La maggior parte delle altre opere che portano l’attribuzione di Annibale, di questi anni a Roma, rivelano una diluizione più evidente con l’opera degli assistenti o una mancanza di ispirazione che sembra derivare dalla sua crescente depressione. Ma le persone che lo circondavano evidentemente erano poco schiette su quello che usciva dalla sua bottega. Una domanda che sorge è quanto furono dovuti all’incoraggiamento di Agostino, la più raffinata presentazione e il tono classico di alcuni dei lavori da stanza, come l’Incoronazione e il Domine, Quo Vadis? la mano del quale è stata anche vista negli studi per la scelta di Ercole e nei dipinti del Camerino.

Gran parte del dibattito è incentrato sul Camerino; per alcuni è il primo progetto a Roma, iniziato quasi prima che Annibale arrivasse nell’autunno del 1595, per altri è stato fatto contemporaneamente alla Galleria. E sebbene recentemente Francesco Mozzetti, supportato in modo sostanziale da Roberto Zapperi, abbia sostenuto che il progetto del Camerino è quello che Annibale svolse subito arrivato a Roma, perfino prima dell’agosto del 1595; ci sono molti argomenti contro questa tesi, che sono stati ben provati da Silvia Ginzburg in un suo recente studio. Agucchi, e a questo riguardo anche Malvasia, e anche Bellori hanno ricordato che il Camerino è stato realizzato durante un’interruzione del lavoro sulla Galleria. In secondo luogo, il cardinale Farnese nella corrispondenza del 1595 con Fulvio Orsini (8 e 22 agosto), parla della decorazione di stucchi che voleva nella camera in questione e che evidentemente era stata avviata prima che lasciasse Roma (4 luglio) visto che la decorazione stessa è di finto stucco; sembra improbabile che Annibale avesse preso questa iniziativa per conto suo e subito dopo la sua residenza a Palazzo Farnese (è il 4 novembre prima che Odoardo si riferisca alla presenza di Annibale). Quindi qualunque cosa fosse, questa non era la decorazione del Camerino. Poiché si era lamentato a Reggio Emilia l’8 luglio che aveva bisogno di una mano che completasse l’immenso quadro dell’ Elemosina di San Rocco, al quale aveva lavorato per quasi otto anni, è improbabile che arrivasse a Roma abbastanza presto per iniziare questa camera che era evidentemente in corso prima che il Cardinale lasciasse Roma all’inizio dello stesso mese, lasciando dubbiosi sul fatto che la corrispondenza sia veramente legata a questo progetto; possiamo ricordare che Agucchi parlava di più di una piccola stanza che i fratelli dipinsero a Palazzo Farnese, oltre alla Galleria. In terzo luogo, il Camerino è una decorazione che, ancor più della Galleria stessa, mostra la presenza di due mani, uno delle quali di Agostino: gli stili contrastanti di alcuni disegni e le invenzioni alternative, parlano di questa soluzione con problemi di attribuzione. Se alcuni recenti studiosi hanno tentato di escludere la mano di Agostino, questo non è condiviso da tutti: ad esempio Longhi che vedeva un ‘intervento massiccio’ dal fratello maggiore, anche nella scelta di Ercole stesso. Gran parte della decorazione è a chiaroscuro o in grisaille cui Agostino si dedicava particolarmente (prima di superare la sua reticenza sul colore) e comporta l’adattamento dell’idioma grottesco a una modalità classica che si trova anche nelle incisioni che fece e che non sono in nessuna parte in Annibale. Un altro elemento, sottolineato anche dalla Ginzburg, è che i riferimenti classici e quelli a Michelangelo e Raffaello, riconosciuti nel Camerino, devono essere frutto della lunga familiarità con l’antica e grande arte di Roma che non era ancora parte del modo di vivere di Annibale. È infatti più facile vedere la continuazione della sua invenzione naturalistica come imbrigliata dall’esperienza classica che il fratello perseguiva. Se questo fosse una conseguenza di un’alleanza creativa con il residente antiquario Fulvio Orsini, che abitava al piano di sopra, era una discussione che Agostino potrebbe avere avuto, per la sua erudizione uguale al compito. Agostino era percepito come un poeta erudito, filosofo e matematico, e non tanto come un pittore, ma era un periodo in cui tali facoltà, così come la teologia, erano considerate importanti nella pianificazione dei dipinti. Egli era posto in modo unico, in questa attività familiare, nel poter tradurre filosofia e poesia in forme intelligibili, per la sua vasta esperienza di altre scuole e per il fatto che era anche un artista praticante: suo fratello risentiva della sua interferenza, ma proprio questa ebbe una parte monumentale nella riforma artistica che i Carracci rappresentano. Poiché il ruolo di Agostino aveva più a che fare con la pianificazione, egli non sempre era sul ponteggio e la sua salute non lo consentiva; il suo lavoro era, per un artigiano come Annibale, talvolta irritante e invasivo. Se Ludovico era sembrato il giusto regista per le scene progettate delle imprese del duca Alessandro nella Sala Grande, sarebbe stata l’erudizione di Agostino che lo rese unico candidato al soggetto classico del Camerino e poi alla Galleria.

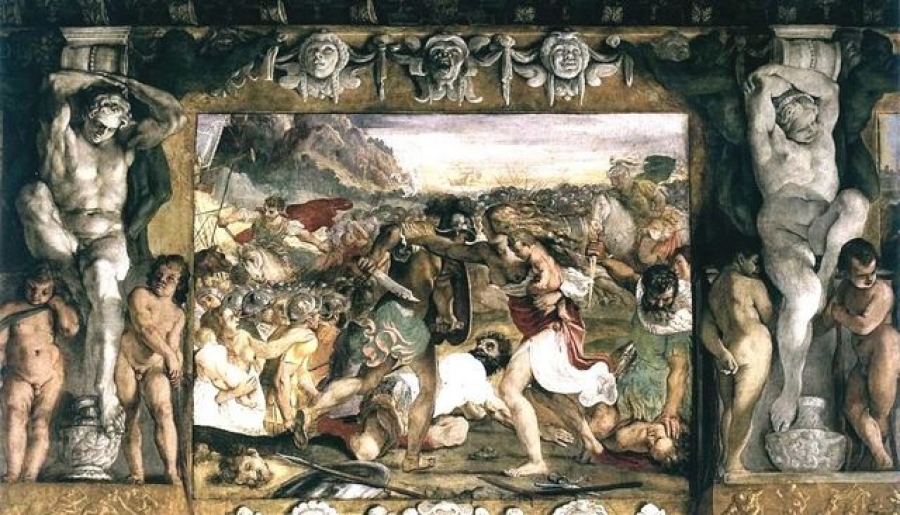

Così egli “andò a trovare Annibale a Roma per aiutarlo nella Galeria” come ci dice Bellori (1672, p. 110). Riguardo alla Galleria Farnese, questo progetto non ha avuto inizio fino al 1597 o al 1598, che è la prima data registrata proprio nella Galleria, sotto l’affresco di Agostino di Glauco e Scilla.

Sebbene Agostino fosse periodicamente assente – ebbe commissioni di ritratti a Parma nel 1597 e nel 1599- era evidentemente presente quando quella data fu scritta sotto il suo affresco nel 1598 e ancora presente a Roma nel periodo del matrimonio tra Margherita Aldobrandini e Ranuccio Farnese (7 maggio 1600) perché è autore di incisioni recentemente scoperte per le epitheliae della coppia; dopo la partenza da Roma Agostino fu impiegato da Ranuccio Farnese a Parma (estate 1600). Se Agucchi afferma che a quel punto “della Galleria in particolare restava a farne la maggior parte”, questo era evidentemente un po’ prima dell’Avviso del 2 giugno 1601, quando fu menzionato il soffitto della Galleria (R. Zapperi, Mélanges 1981, Eros & Controriforma 1994, p. 117), e se prendiamo in considerazione il ricordo di Agucchi, dovremmo considerare la metà dei duecento giorni di lavoro sul soffitto che cadono dopo la sua partenza, ma il contorno doveva già essere stato definito. Ma, come vedremo, la data in lettere maiuscole MDC registra il completamento degli affreschi del soffitto. All’idea di Malvasia (I, 403), che Odoardo (che Malvasia dice essere stato il più irritato dagli eventi che portarono all’abbandono di Agostino) voleva Ludovico a gestire il lavoro a Palazzo Farnese, è stato sempre dato poco ascolto, come pure al suo suggerimento che egli voleva che di nuovo lui riprendesse più tardi (I, 447), tuttavia l’idea che Annibale potesse gestire questi progetti da solo è in realtà piuttosto improbabile, perché l’esperienza di Agostino nei temi classici e nella mitologia sembra essere un ingrediente essenziale per le decorazioni del soffitto e l’erotismo giocoso del loro tenore è completamente consonante con la lettura, l’erudizione e la libido per cui era famoso. Soprattutto Annibale aveva bisogno di una gestione. Suo fratello era evidentemente un perfezionista e una delle ragioni del suo permanente soggiorno in Emilia era la mancanza di completamento, per sua soddisfazione, della pala d’altare con l’Ultima Comunione di San Girolamo, che non venne consegnata fino al 1597.

Le date precise e persino la motivazione per la decorazione della Galleria rimangono ancora poco chiare, perché anche se sembra che Odoardo avesse potuto considerare imminente il matrimonio di suo fratello con Margherita Aldobrandini come una buona scusa per una eccitante celebrazione degli Amori degli Dei, questa unione venne proposta per prima per settembre del 1599 (lei allora aveva ancora dodici anni) e venne a termine con la cerimonia nella Cappella Sistina, il 7 maggio 1600, una cronologia poco verosimile anche presupponendo una lavorazione continuativa (delle 200 giornate) senza eventuali interruzioni impreviste. All’inizio, come Agucchi riferisce (e la sua testimonianza è più vicina al tempo) hanno lavorato insieme in armonia: “E con tutti che cominciassero li due Fratelli que’ lavori, come havesser da toccare ad amendue insieme, senza verruna distinzione, e nel vero vi Si veggono delle cose degne di gran lode, tanto dell ‘uno, quanto dell’ altro”. Ma Agostino aveva trascorso la parte migliore di un decennio raffinando le sue abilità di pittore e voleva dimostrare che anche lui non solo poteva progettare ma anche fare dipinti originali. Agucchi dice che Agostino riconosceva che suo fratello era meglio di lui a dipingere ‘non poco superato da Annibale nel felicemente operare’ e furono i loro disaccordi, apparentemente promossi anche da Tacconi, che lo condussero a lasciare il fratello per completare l’obiettivo; Malvasia concludeva che ciò era il frutto della famosa gelosia di Annibale, specialmente perché l’eccellenza di suo fratello come incisore si mostrava essere accompagnata dal suo contributo pittorico alla Galleria. Agucchi afferma che Agostino lasciò la città con la maggior parte della Galleria incompleta e vedremo che questo fu nel periodo del matrimonio, nel maggio del 1600, molto tempo prima di essere pagato a Parma per i lavori per il duca Ranuccio (dal 1 luglio ). L’interruzione del 1600 potrebbe infatti essere stata causata dalla partenza prematura di Agostino, un ritorno al lavoro seguiva il ripristino delle impalcature rimesse in atto nel gennaio 1601 e forse le pareti finali vennero completate prima dell’annuncio del 2 giugno dello stesso anno in cui gli affreschi del soffitto furono visti per la prima volta. Perché sebbene la data MDC inscritta in caratteri prominenti sotto l’affresco di Polifemo e Galatea all’estremità orientale della Galleria sia oggi invisibile dal pavimento, il cornicione di 1 palmo e 2 /3 (circa 40 cm) che lo nasconde venne messo in atto da Mastro Jacopo da Parma nel 1603, così che ciò ha qualche importanza nel tracciare il completamento della volta. Forse è davvero quello il momento in cui i dipinti del soffitto vennero completati.

English Text

Agostino Carracci and the Galleria Farnese. New Point of view (Part I^)

Agostino was an essential part of the Carracci team and it is unrealistic to belittle the role he played, despite Annibale’s rivalry with his elder and more educated sibling that meant that he wanted all the fame of the Galleria. Mancini’s account and that of Agucchi, are precious because they are records of people who knew them both, for even Baglione’s account (1642) seems to be coloured by the passage of time and an unfamiliarity with the protagonists, while Bellori is from the next generation altogether, and Malvasia had a wholly Bolognese take on their careers. The gist of Agucchi’s account is that the two brothers undertook the work – by implication all the decorations at Palazzo Farnese and some oil paintings – in harmony, until disagreements meant that the elder one left when the greater part of the Galleria remained unfinished. The anecdote of Cavedone’a account of the first drawings for the Triumph of Bacchus Annibale sent to the Carracci studio in Bologna, to show what he could achieve without his brother’s direction, has not been taken into consideration. It shows that he first thought of the decoration in the Galleria as a continuation of the type of frieze design that had been so successful at Palazzo Magnani, and the subsequent allocation of the Triumph of Bacchus to the centre of the vault, with Agostino’s two scenes on either side, can be attributed to the latter’s revision of the original project, and in fact Annibale had spent as much as three years in Rome without resolving the design or embarking on any major project. Some basic assumptions need to be queried: he was not necessarily the polymath who had all the iconography and quadratura at his fingertips, and the command of classical mythology was something he did not show previously, understandably he needed prompting, And although Federico Zuccari was claiming the right for painting to be numbered among the liberal arts in a campaign that would ultimately meet with some success, there is quite a body of evidence to suggest that Annibale regarded himself as a pittore, an artisan whose manual dexterity was his claim to fame, and his relegation by the Cardinal to lodgings in the attics of Palazzo Farnese, very much in the service quarters, is acknowledgement of a humble status that his subsequent fame cannot erase. Like Caravaggio, Annibale does not even seem to have belonged to the Accademia di San Luca, nor to have been a man of learning. By contrast the need prevailing in the Cinquecento to have a letterato translate the intentions of the patron in a language that the artist would understand was met in a singularly innovative fashion by Agostino, obviously at ease in both worlds in a way that the likes of Bishop Paleotti, Melchiorre Zoppio, or even Giovanni Baglione, could never achieve. Annibale evidently needed his brother’s co-ordination and diplomacy, but when this developed to the point that the latter was competing for artistic recognition on the ceiling itself, there were bitter words and the impatience he had for his interference boiled over. In reality there had been a long history not only of Agostino’s guiding role in the business, it was also quite normal for Annibale’s paintings to be seen as needing tidying up as they had been judged too ‘messy’. There was ample stope for disagreement, but it was also the design of further paintings, like the Sleeping Venus now at Chantilly, that formed the background of the acrimony between the two brothers that eventually led to Agostino’s departure that year. Annibale resorted more and more delegating to his favourite pupil for the finishing touches, and it must have been this that enabled to finish the bulk of the ceiling, for it can be argued that main part of it was complete by the end of 1600.

Without underestimating the incredible ability Annibale had for capturing a new naturalism, and a facility with the evocation of expression, we should also recognise that the comprehensive decoration that the Carracci offered was a joint production, in which the separate talents of each of the brothers (and in Bologna, their uncle Ludovico) were complementary. The individual contributions of each in the Palazzo Magnani frieze were indistinguishable, ‘l’abbiamo fatto tutti noi’, and to a certain extent each could replace the other, each could do preparatory designs and drawings, as they could also finish each others’ paintings. In our concern to recognise the genius of the artist most identified with the Farnese Gallery we have ignored this basic consideration, that it was a collective and co-operative enterprise that stemmed from the talents of the two brothers. A little like a couple who come to be perceived as less than complete personalities without the other half, we do get the impression of two people that were also opposite and sometimes completely at odds, and this did finally lead to a complete breakdown – for both brothers. And while the dominant impression is of the virtuosity of the brushwork of Annibale because of its sheer brilliance, a production like this was as much down to design as to execution, and he was in reality the younger brother in this partnership. That there was jealousy between them is a commonplace; ‘what (Annibale) could not put up with was to have to hear everyone also constantly saying that he had been beaten by Agostino even in painting – in the sureness of handling of the large contour and in a judiciousness and copiousness of invention’ as Malvasia recalls. In modern times the solution of who wrote the programme for the Galleria been a continuing conundrum, the realisation that it genuinely was a joint production, with one brother providing the script and the other translating it into paint is a much more probable solution than an unknown literary author providing them with texts would be. But we can see which one sexed up the classical stories, and made the paintings titillating. There was no need for a key to the mythology and the allegories that were implied, as their author was present on the spot and ready to answer queries as they arose, having already used texts like Ovid’s Metamorphoses to teach young artists in Bologna about ‘invention’. The Latin titles that accompany the scenes in Palazzo Fava become less long-winded and literary in Palazzo Magnani, and even more pithy in Palazzo Farnese, but they are the result of a learning that Annibale did not possess. It was not to be a libretto in Rome but it could not be done without the erudition that Agostino was endowed with, and his character explains the humorous interpretation of the classical sources that we see in all the narratives. But if he did make a programme, the thinking behind it was interrupted by the quarrel that came to a head when the actual painting of the ceiling was less than half complete, and while some inventions were evidently alternates pressed into use after Agostino had left, the completion of the walls done years later could not continue the same inspiration, so accounting for the discontinuity of invention that has always been noticed in the finished decoration. This does mean that we should be looking in the drawings for the Galleria, as never before, for suggestions of unusual iconography, for alternate designs that were not adopted, and for graphic idiosyncrasies that are attributable to Agostino. There are several mentions of what was a pact between them that privileged Annibale’s brushwork, and at the same time it was understood that he did not always need to do preparatory drawings, so we can perhaps begin to discern the usually harmonious division of labour between them.

It may be possible to recognise some of Agostino’s suggestions for the framework of the Galleria, and also other designs relating to the frescoes, sometimes mistaken for Annibale’s initial thoughts for the various subjects because of the very different figurative solutions that he ultimately reached. None of the modern studies of the drawings have fully defined their differences, and because flawed connoisseurship started even during his lifetime and continued unabated because of the commercial merits of exploiting the great fame the Carracci achieved, it is exceptionally difficult to demarcate between their styles. Most of the biographical information we have is from a generation later, contaminated by the optimistic marketing of what remained that was moveable, and saleable. The prevalent view that Annibale was somehow responsible for the whole enterprise is manifestly exaggerated, and the tenor of learning, of intellectual repartee and playful enjoyment of classical antiquity and modern sexuality that colour it has more to do with his brother’s personality. The difference in their roles is in reality self-evident, and while we rightly appreciate the extraordinary versatility that Annibale’s handiwork evinces, the need for direction was still very much more significant in the eyes of the contemporary patron; and this was not the usual Christian allegory. It is more reasonable to suggest that his brother was not only responsible for decorative detail, but was the architect of the whole, the inventor of the counterpoint of narratives and the alternation of fictive materials, and the intellectual mainspring of the narrative that flowed from the intellectual debate that he had with the patron and his court. It must be Agostino who made the classical myths accessible and intelligible, translating into a visual anthology the dry narrative that his antiquarian friends had assimilated, and he added to them the spice of sex that was irresistible. He was in a unique position in being able to mediate between the antiquarian expertise of Fulvio Orsini, the literary scope of Michelangelo’s and Tasso’s poetry, and that of so many other authors, and the range of artistic styles that he had familiarised himself with during his career as a reproductive engraver. He would have been the cicerone who was able to explain to a Roman audience the nature of the Venetian school of painting of which the Curia had become aware following Clement VIII’s takeover of Ferrara in 1598. Certainly what we know of his ability with caryatids and supporting figures, often in grisaille rather than colours, coincides with the role that he seems to have assumed in designing the framework from Palazzo Fava onwards. His long concentration on graphic media, drawings and engravings, was frequently interpreted as unwillingness to compete with his brother’s virtuosity in the medium of paint, but he gradually assumed more responsibility until he could finally contribute in active competition with him. The oversight that he had over the project in hand meant that Annibale had less need to make preparatory studies, so much so that Agucchi said he worked without any.

It is Mancini who makes it clear that Agostino had come to Rome ‘per condur la galleria di Farnese con il fratello’ and this, it can be argued, was to direct the project with him. Condurre was what Albani did for the series of lunettes in Palazzo Aldobrandini, and for the decoration of the Herrera chapel in S. Giacomo degli Spagnoli, and it is management that would often be undertaken by pittori who did not in fact always execute the major narrative scenes, as Agostino Tassi in the Sala delle Muse in Scipione Borghese’s pavilion at the Palazzo di Montecavallo, or Pietro Paolo Bonzi at the Villa Chigi at Castefusano. They were responsible for the task of co-ordinating the overall plan, for setting out the major divisions and deciding what intervening decoration, grotesques and landscape elements, should be inserted. This was after all what the Bolognese painters had a reputation for, designing quadratura and generally planning schemes of decoration that incorporated fictive sculpture and architecture as a setting for narrative scenes, as well as the perspective inside them, landscape panels and grotteschi.. Agostino’s asthma and being overweight meant that he found it really difficult to work in fresco, but his learning was not the only characteristic that made him so important for the planning of the work, he was also much more conversant with patrons and courtiers and could communicate with them. His understanding of classical history and mythology had already been the underlying knowledge behind the decorations the family had undertaken in Bologna. The director’s role attributed to Agostino is in fact implied by the designation of Annibale and his companions as pittori in the Farnese household.

Agostino certainly arrived in Rome after the Galleria project had been started, because Malvasia in one of the notes associated with the Felsina Pittrice relates that Annibale had sent the drawings of the Triumph of Bacchus to Ludovico in Bologna from Rome, so that his uncle could see how he was managing without the advice and help of Agostino, for he suspected that the world would not give him all the credit for what he achieved. The note is one that Malvasia jotted down from conversations with Ludovico’s principal assistant Giacomo Cavedone, but does not seem to have used in the Felsina itself, nor has it been considered in the context of the rivalry between the brothers. Born in 1577, Giacomo had first met Annibale in 1589 when he was twelve, and joined the Carracci school in 1591, and he seems to have been well thought of by them, as he excelled in bacchanals (baccieggiava). In this fascinating anecdote that has largely been ignored, he recalled that Annibale was fearful that people would think that his work in Rome would be considered the result of his brother’s direction and guidance – direzione ed appoggio. And he did not want him at Palazzo Farnese, even though Agostino had offered to work always following his cartoons, and to be in essence his servant. Down in Rome on his own he wanted to confound his brother or at least show what he could achieve without his help. Apparently Annibale had sent the drawing, in three sections, (tre fogli reali dissegnati di penna grossa ed ombreggiato di lapis nero) to Ludovico in Bologna, in other words to his uncle rather than his brother, because he was afraid that people would think that he could not have done it and that it would be seen as the result of Agostino’s invention. The drawings were in broad pen and ink, and black pencil (often described today as ‘black chalk’ but usually charcoal). The work impressed Ludovico and he had it copied (by Cavedone) before forwarding it to Agostino in Parma – as if it came directly from his brother – because he wanted to surprise him or at least to show him what Annibale could do without him. It rings true because the first designs for the Farnese ceiling are in the character of a frieze – with the Triumph of Bacchus divided into three separate episodes – and dominated by the design of the walls rather than the vault itself, so continuing what had been a very happy solution at Palazzo Magnani, where the ceiling is flat with beams, and the decoration painted at the top of the walls. Unfortunately neither the drawings that Annibale sent to his brother, nor the copy Cavedone made of them (that Malvasia himself apparently owned) , nor the copies by Sebastiano Brunetti that Malvasia refers to, have survived. A drawing that echoes the description (and may be one of these versions rather than Anninbale’s original) is the large sheet in the Albertina of a Bacchic Procession, with much white highlighting, generally regarded as an early design for the Triumph of Bacchus that was not adopted. The story gives weight to the idea that Annibale was in some sense dependent, or regarded as relying on Agostino’s direction, and suggests indeed that the learning that he undoubtedly had was used in the family business to guide the younger brother at least in the choice of subject and the content of the pictures he painted, while the latter also evidently resented this oversight of his work. The anecdote therefore reinforces the impression of the kind of collaborative effort that had graced previous decorations by the Carracci, and although we do not yet understand the chronology of this episode, nor even of the Galleria itself, it is clear that the mythology of the many scenes there relied on an erudition, and a plan, that was not within Annibale’s remit but which was certainly a part of the Carracci’s reputation as a family business. It does seem possible that Annibale was actually incapable of managing the major projects he was hired to complete, and needed his brother – il dotto fratello che gli dirigeva il lavoro e li dimezzava la fatica’ – not only to supply the iconography, but also to plan the day-to-day work. And if the initial designs, described by Cavedone, were for a radically different arrangement with the Triumph of Bacchus on the wall rather than at the centre of the vault, Agostino must have had a major part in the eventual re-arrangement, when he secured the two scenes on either side of the central panel, which for a long time would be the only parts he was remembered for. One of them has the date 1598 underneath, so at that stage many design features of the ceiling must have been quite advanced.

Many attempts have been made to circumscribe Agostino’s participation in the ceiling because of his arrival in Rome after a portrait commission in Parma 22 October 1597, and another similar commission in July 1599 again in Parma., which would limit his work on the Galleria to that period. The length of Agostino’s presence in Rome is not certain, but Malvasia says that he would have deserved the credit for half if not the whole of the merit for the Galleria ‘sariasi attribuito almeno la metà, se non tutto l’onore della Galeria Farnesiana, già che tutta Roma applaudiva tanto…’ (Felsina Pittrice, 1841 ed. I p. 403). Mancini, who knew them both and their health issues, said that their rivalry meant that Annibale wanted the glory of the production to himself, adding in a further note – all the glory, but gave a vivid idea of his brother’s profondissimo sapere, that he was a man of ‘singularissimo giuditio’. Agucchi, who is as near as we have to being a witness of the course of events, says that they began in harmony ‘come havesser da toccare ad amendue insieme, senza veruna distintione’ (D. Mahon Studies in Seicento Art and Theory, 1947, p. 245/55) but after disagreements that were fostered by someone who enjoyed seeing them set against each other, Agostino left when the greater part of the Galleria was still to be completed and went back to Bologna and then to Parma, but not until the time of the Aldobrandini/Farnese wedding (May 7 1600). The anecdote about the drawings Annibale sent from Rome is important because it reveals Agostino’s perceived role in production inside the Carracci business, which the younger brother resented and consistently downplayed. Agostino’s role in the actual painting at Palazzo Farnese was limited, for he not only (here we have Agucchi’s words to that effect) recognised that his brother could paint better, but also his presence in Rome was evidently conditional on his playing second fiddle. Like the words of Mancini and Agucchi, Cavedone’s recollections that were relayed to Malvasia are important because they are voices of eyewitnesses in events that would later be subject to all manner of interpretation by people who were not present at the time.

Duke Ranuccio’s contact with the Carracci was evidently through Agostino, initially as an engraver as early as 1591; he was realistically the point man in the family for recruitment by such a powerful patron. In terms of chronology, Odoardo Farnese, who had been planning since 1593 to bring the Carracci down to Rome to paint in his palazzo and wrote from Rome 21 February 1595 to tell his brother (in Parma) that he had decided to have the ‘pittori Carracci’ paint the Sala Grande of the palazzo with the imprese of their father the late Duke, and they had already been to Rome some months before on an exploratory visit. He needed the book (left behind with the effects of Conte Masi) with drawings of the campaign in Flanders in order for the pittori to start. The Carracci had done several decorations in Bologna, and Malvasia reports (I, 295) that Ludovico was to direct the work, bringing Annibale with him (and he said he had a letter from the Duke to that effect). The decoration of the Gran Salone celebrating Alessandro’s exploits in Flanders did not happen because there was no book of words: the Camerino and the Galleria Farnese did not proceed likewise because of the absence of the iconographer; the archaeologist Fulvio Orsini was not able to provide the necessary blueprint for the pittori. Malvasia says that Agostino followed Annibale to Rome, ‘ V’andò dico, e poco dopo vi andò Agostino’ (I, p. 295), and the problems suggested by Annibale’s drawings must have meant that Agostino finally left Parma and joined his brother in Rome. There has always been great praise for all the thinking and direction that the elder brother was famous for: the elephant in that room is indeed Agostino.

The collaboration was evidently had been at its best when it was moderated by the brothers’ cousin Ludovico, and when Agostino’s talents were taken up in absorbing so much of others’ work in the reproductive engraving career that assumed the greater part of his time in the 1580s. But he enjoyed the glory of the fresco cycles in Bologna, and increasingly participated in their invention, particularly it seems in the planning of the whole interior, with a particular enthusiasm for the caryatids and other framing motifs in grisaille for the narrative paintings, which however became more dominant as the Carracci firm became more confident. Malvasia contrasted the diligence of Agostino versus the impatience of Annibale, and there had long been trouble with the latter’s modo impaziente e poco pulito , for the early altarpieces had often aroused criticism for their loose handling. There had always been an element of a need to correct the more instinctive and flamboyant brushwork of the younger brother, which was seen as not possessing an acceptable finish, and Annibale had evidently accepted this ‘correction’; Ludovico had apparently to tidy up the work in the Fava frescoes. Whether or not we would regard this as a defect is moot, but Annibale (who was a proverbially down-to-earth character) also needed a manager for he found it difficult to deal with clients, while Agostino was well-read and conversed with a different class (Malvasia I 265, 327/8). From a personal point of view, Agostino evidently loved his brother to bits, svisceratissimamente, as Mancini relates, but this seems a protective affection that alternated with impatience bordering on intolerance (from Annibale’s point of view) for a personality that was the opposite of his own.

We are used to being reminded of how busy Annibale was in Rome from Bonconte’s vivid account in August 1599, when Agostino was apparently away, but it is also true that prior to Agostino’s arrival in 1597 or early 1598 very little had happened, and Cardinal Farnese could well have been dissatisfied with the productivity of the Carracci team he had hired. In the nearly three years that Annibale was in Rome on his own, from the autumn of 1595, nothing was done to execute the major decoration apparently intended in the Salone of Palazzo Farnese, and the Camerino was not yet started (it was still underway at the turn of the century); it is reasonable to suppose that the Galleria itself only was started after Agostino arrived and it was then that work really got going. There is almost as much mystery in what Annibale was up to in Rome, as in the dark years of Caravaggio after his last appearance in Lombardy in 1592, and his first employment by Lorenzo Carli in the winter of 1595/96. What did his art really represent when he arrived in Palazzo Farnese? he had brought with him the Holy Family with St Catherine (Naples, Capodimonte) done ten years earlier, and he painted the Christ and the Canaanite Woman for the chapel of Palazzo Farnese which retains a more Ludovichian character, perhaps due to the latter’s familiarity with Correggio’s painting of the same subject. It looks like a picture planned in Bologna but done in Rome, almost as though Ludovico had provided the design on his departure from Bologna. And although this goes against the idea of Annibale’s originality, we should recall that Ludovico as the Carracci manager had provided Annibale with designs before, as with the Pietàs in Reggio and Parma, where Malvasia records that the elder Carracci was ‘il più copioso e feroce in invenzione’; and that Annibale’s work frequently needed revision (I, p. 345). Although he was presumably always drawing, and volunteering sketches for those actually around him, nothing was seen in public from Annibale’s hand until the St Margaret was placed on the altarpiece of his chapel in Santa Caterina dei Funari in 1600. This was actually only a copy of part of a much earlier altarpiece in Bologna, with which Gabriele Bombasi had been involved, and the patron (who had moved to Rome) was evidently nostalgic for this kind of painting. It is a figure adapted from a saint Catherine in the altarpiece (Paris, Louvre) that Annibale had done eight years earlier for the Cathedral in Reggio Emilia, and it was Lucio Massari who made it in Bologna, and if it was retouched by Annibale after it reached Rome; it was certainly not a new creation. But it was a relevant subject for a Farnese courtier at the time Margherita Aldobrandini was booked to be the Farnese bride. It was also probably at this time that Odoardo Farnese got the idea of having Annibale repaint the dome of the Gesù, doubtless in emulation of the Correggio dome in Parma: in 1599 he was sponsoring the building of the Casa delle Professe at the Gesù, and he had an apartment just beyond the dome itself. Bombasi, who had been Odoardo’s tutor after a long patronage by Ottavio Farnese, was evidently nostalgic for the ‘Venetian’ character of Annibale’s work in Bologna, and for the Correggios and Titians he had had him paint copies of. These copies were bequeathed to Odoardo on Bombasi’s death in November 1602 (many courtiers expressed their loyalty with this kind of bequest) and their unwrapping was doubtless the occasion that Boschini described when the Cardinal produced a group of Venetian paintings that were supposed to be by Correggio, Titian and Parmigianino – only to be revealed as the work of Annibale. The Correggesque tenor of Bombasi’s taste is illustrated by his painting that Annibale did for him of the Archangel Gabriel surrounded by Angels, now in Chantilly, and as a courtier close to the Cardinal he might well have been the inspiration behind the idea of repainting the dome of the Gesù, one of the major projects that was planned for Annibale to do after the completion of the Galleria. But like so much of what Odoardo planned with his painter, it came to nought, and we are left with only a few pictures that the artist did when he lived at Palazzo Farnese.

The paralysis of Annibale’s directional and inventive faculties both before Agostino’s arrival in Rome, and after his departure in 1600, can be read as evidence of the important role that the latter played in all the Farnese decorations. For the Galleria is not a casual assemblage of the loves of the Gods, but a careful choice of mythology brought to life, matching what Sallust said of myth, that it is something that never was, but always is. The literary preparation Agostino had, and his intercourse with the intellectuals of his time, combined with his superlative experience of others’ work demonstrated in his engravings, made him an essential cog in the Carracci business, and the architect of its transformation. Annibale, in contrast, was an intuitive individual, who had a limited education and more than once declared his impatience with his brother’s pedantry and the courtiers whom he brought along to discuss the task in hand as he painted. We should not assume that these visits were not without effect, that the humble painter at work on the scaffold was able to dismiss their comments and carry on regardless. His brother was demanding and as Mancini says ‘di singularissimo giuditio che, qualsivogli minimo errore {d’arte}, subito lo riconosceva, et al fratello, che amava sviceratissimamente, stando a veder operare, le diceva qualche cosa, mal volentier sentita da Anniballe, o che non fusse vera o che non volesse questa superiorità’ . The great learning that all the sources attest to was not going to be dissipated in mere ornament and decoration, although this may be the most prominent manifestation of his designs. And with the experience of the studies associated with the Tazza Farnese, where Agostino is so concerned with the decorative surround, we should indeed be looking for designs where there are frames and motifs for the spartimento of the decoration, the challenge of the division of the vault of the Galleria into sections. The existence of at least one drawing by Agostino for the Eros and Anteros Cupids of the angles of the vault, on the verso of the study for the Tazza in Chicago, shows that he was involved in this important iconographic feature, which for Bellori was a key to the whole subject matter of the Galleria.

There would still be a few paintings in which Annibale’s self-assurance still shines, but they are mostly cabinet pieces, like the Domine, Quo Vadis, that Pietro Aldobrandini acquired when he visited and saw the completed ceiling in 1601, the St John the Baptist done for Corradino Orsini probably at the same time (an evidently brilliant work that is still lost, although known from an engraving and a copy), the Pietà in Naples, another small copper now in Vienna of the same subject, the Three Maries at the Tomb in the National Gallery in London, another great edition of same subject now in St Petersburg done for Lelio Pasqualini, a Bolognese antiquarian, who was Canon at Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome. This and the Coronation of the Virgin (Metropolitan Museum, New York) that was evidently secured by Pietro Aldobrandini, probably during the time of rapprochement with the Farnese because of the union of the two families in 1599/1600, demonstrate the Correggesque and Venetian flavour that was expected of Annibale in his Roman stay. Some of this was satisfied with reminiscences, like the Saint Margaret he provided for Gabriele Bombasi referred to above, and the Christ and the Woman of Samaria, a reduced version of the composition in the Brera done in 1593/94, now done for the Oddi family in Perugia. Another is the little Vision of Saint Francis, at present in Ottawa, which is rightly associated with its background that resembles the architecture of Palazzo Farnese. These collectors were fortunate: even the wealthiest enthusiast of Bolognese painting, Vincenzo Giustiniani, who with his brother Cardinal Benedetto had come into their inheritance with the death of their father Giovanni Giustiniani (died Jan 9th 1600) had no success in obtaining a work by the master himself, although he continued to employ the Bolognese painters (Albani, Domenichino, Viola) to decorate his country villa. Most of the other works that bear Annibale’s attribution, from these years in Rome, reveal more evident dilution with the work of assistants, or a lack of inspiration that seems to have stemmed from his increasing depression. But the people around him evidently were less than candid about what came out of his workshop. A question that arises is how much the tighter presentation and classical tone of some of the cabinet works, like the Coronation and the Domine, Quo Vadis ? was due to the encouragement of Agostino, whose hand has also been seen in the studies for the Choice of Hercules and in the paintings of the Camerino.

Much of the debate is centred on the Camerino; for some it is the first project in Rome, started almost even before Annibale arrived in Rome in the autumn of 1595, for others it was done concurrently with the Gallery. And although recently Francesco Mozzetti, supported notably by Roberto Zapperi, have argued that the Camerino project was what Annibale turned to immediately he arrived in Rome, even as early as August 1595, there are a number of arguments against this, which were well rehearsed in Silvia Ginzburg in her recent study. Agucchi, and for that matter Malvasia, and also Bellori recalled that the Camerino was done during an interruption of work on the Galleria. Secondly, Cardinal Farnese in the 1595 correspondence with Fulvio Orsini (8 and 22 August) that has been drawn in to the argument speaks of the stucco decoration that he wanted in the camera in question that evidently had been started before he left Rome (4 July) whereas the decoration itself is of feigned stucco; it seems improbable that Annibale would have taken this initiative on his own, and immediately on taking up residence in Palazzo Farnese (it is 4 November before Odoardo refers to Annibale’s presence there). So whatever this was it was not the decoration of the Camerino. As he had complained in Reggio Emilia on 8 July that he needed a hand completing the huge painting of the Elemosina di San Rocco that he had been working on for almost eight years, it is unlikely that he arrived soon enough to have begun this camera in Rome that was evidently in progress before the Cardinal left Rome at the beginning of the same month, so casting doubt that that the correspondence really relates to this scheme; we can recall that Agucchi spoke of more than one little room that the brothers painted at Palazzo Farnese, apart from the Galleria. Thirdly, the Camerino is a decoration that, even more than the Galleria itself, shows the presence of two hands, one of them Agostino’s: the contrasting styles of some of the drawings, and the alternate inventions, speak of this solution to attributional problems. If some recent scholars have tended to exclude Agostino’s hand, this is a phenomenon that is not shared by all: Longhi for instance seeing a ‘un intervento massiccio’ by the elder brother, even in the Choice of Hercules itself. Much of the decoration is in the chiaroscuro or grisaille that Agostino in particular embraced, (before he overcame his reticence about colore) and involves the adaptation of the grotesque idiom to a classical mode that is also to be found in the engravings he did, and no-where in Annibale. Another element, also underlined by Ginzburg, is that the classical references, and those to Michelangelo and Raphael, that have been recognised in the Camerino must be the fruit of long familiarity with the antique and great art in Rome, which was not yet part of Annibale’s way of life. It is in fact easier to see the continuation of his naturalistic inventiveness as being harnessed by the classical experience that his brother pursued. If this was as a result of a creative alliance with the resident antiquarian Fulvio Orsini, who lived on the next floor, this was a discussion that Agostino would have had, for it was his erudition that was equal to the task. Agostino was perceived as an erudite poet, philosopher and mathematician, and not so much as a painter, but this was a period when such faculties, as well as theology, were held as important considerations in the planning of paintings. He was uniquely placed, in this family business, to translate philosophy and poetry into forms that were intelligible because his wide experience of other schools and the fact that he was also a practising artist: his brother resented his interference but it was to be a monumental part of the artistic reform that the Carracci represent.