di Clovis WHITFIELD (with English text)

Gli Amori che Agostino Carracci dipinse a Parma, nella galleria del Palazzo del Giardino, ricordano altri eseguiti a Roma, e i più celebri sono quelle coppie di Eros e Anteros negli angoli della Galleria Farnese. Questi amorini che lottano erano per Bellori la chiave di tutto il soggetto della decorazione a Palazzo Farnese, ed è possibile credere che questa invenzione geniale sia nata dall’ingegno naturale di Annibale per celebrare l’unione politica tra le due casate sigillata non solo con il bacio degli sposi. Non si sa di preciso se Odoardo Farnese avesse in mente le nozze del suo fratello (7 maggio 1600) quando commissionò questa decorazione con gli Amori degli dei, ma in ogni caso le scelte di scherzi sapienti e di fantasia pittorica erano incredibilmente adatte, non solo anche perché poteva avere il meglio di due ingegni in una produzione che sarebbe stata il canto del cigno dei due fratelli, una collaborazione talmente felice che ancor oggi è quasi impossibile decidere chi abbia fatto quali elementi. Si tratta di una impresa miracolosa che dà l’impressione che i due fratelli si muovessero in un’unità operativa talmente efficace che per contro non avrebbero potuto operare singolarmente.

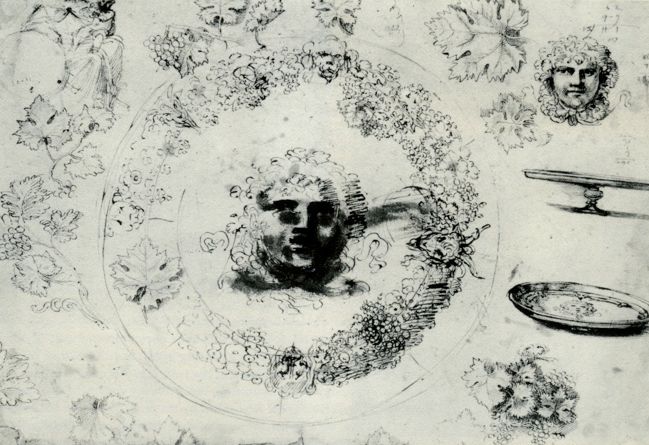

Ma questo sarà prima, dato che in questo saggio studiamo prima l’ultimo, e poi alla fine l’altro, al come nella parabola dei lavoratori nella vigna. Il tema degli amori è comunque più vicino alla superficie, dato che ce ne sono diversi anche dopo quelli dipinti nella Galleria. Tra i progetti decorativi dove tutti e due i fratelli erano coinvolti vi è la Tazza Farnese e la decorazione della spinetta (clavicembalo), di cui alcuni elementi sono oggi alla National Gallery di Londra, e questi sono collegati attraverso gli amorini che raccolgono l’ uva per Sileno e che sono variazioni sullo stesso tema di Eros e Anteros. La Tazza e il Paniere Farnese costituivano effimere decorazioni da tavola, e possiamo credere che siano nati unicamente perché il cardinal Odoardo aveva a sua disposizione questi pittori talmente bravi che potevano non solo inventare ma anche creare questi oggetti di argento da tavola e anche a dipingere strumenti musicali come il clavicembalo che da molto ha smesso di suonare ma che continua a incuriosirci. E tuttavia né la Tazza né il clavicembalo furono commissionati per il cardinale Odoardo, essendo quest’ ultimo stato creato per Fulvio Orsini, mentre l’argento fu lavorato per un cortigiano spagnolo a Palazzo Farnese. Agostino si prestava facilmente a lavorare questo materiale, essendo il miglior incisore dell’epoca, e condivise questa commissione con un altro incisore, Francesco Villamena da Assisi, che aveva il compito di incidere il paniere Farnese. La Tazza venne era eseguita per il più intollerabile dei cortigiani che tormentava Annibale, attraverso il fratello Agostino, cioè quel Don Juan de Rosas, noto, secondo il Malvasia, come Don Giovanni di Castro spagnolo,conosciuto per aver dato ad Annibale quei miseri 500 scudi che calcolò gli fossero dovuti, dopo aver sottratto il costo di vitto e alloggi, come compenso per il lavoro della Galleria Farnese. (n.19)

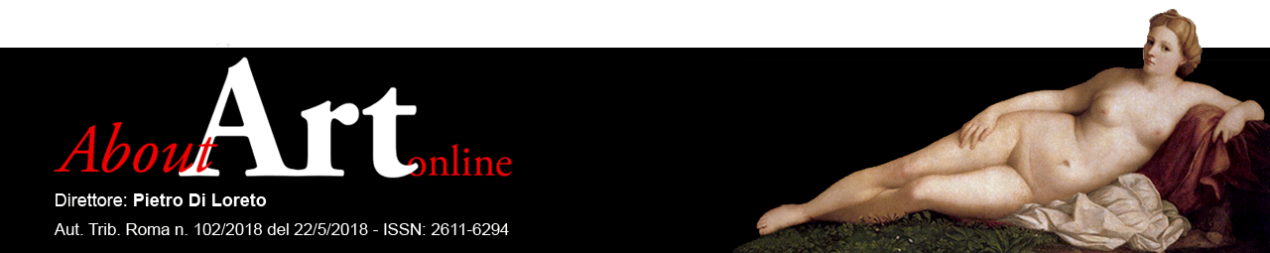

Agostino Carracci, Two cupids picking grapes Frankfurt, Städel Museum

E ancorché la Tazza stessa, ora ridotta in un semplice disco, sia stata sempre riferita ad Annibale, ci dev’essere un dubbio forte se l’incisione stessa fu eseguita da lui o dal fratello maggiore. La maggior parte dei disegni noti sono tradizionalmente attributi ad Annibale, ma è abbastanza palese che diversi non lo sono, mentre invece nel progetto trapela l’estensione della loro collaborazione. Certi fanno parte della decorazione e con giovani che colgono le grappoli d’uva, altri sono studi per figure.

Here attributed to Agostino Carracci Spinet cover London, National Gallery

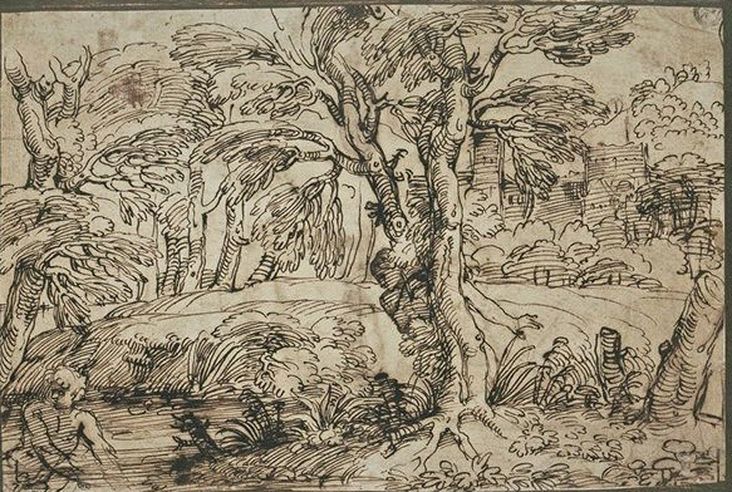

E capita che gli amorini che si arrampicano sulla pergola attorno al gruppo di Sileno rinfrescato da un otre che compaiono sulla Tazza, siano gli stessi sulla vite del coperchio del clavicembalo (National Gallery, Londra) – una commissione per un altro cortigiano Farnese. Il disegno per queste figure, illustrato in copertina del catalogo della mostra a Washington del 1999/2000, è citato (n. 20) di recente per essere un esempio clamoroso della mano di Agostino, con tutto il suo carattere di ombreggiatura a linee ripetute e incrociate e un disegnare che segue la libertà della penna. Questo disegno, ora a Francoforte, era stato evidentemente diviso in due, forse per facilitare il trasferimento sul coperchio del clavicembalo, e poi unito per creare un insieme col paesaggio che unisce i due lati. Dalla conoscenza dei dipinti di figure di Parma, è facile di capire che la pittura del clavicembalo non sia di Annibale ma del fratello, il quale aveva fama di eseguire dipinti su piccola scala, e Fulvio Orsini, per il quale era stato eseguito, era l’antiquario di Palazzo Farnese con cui Agostino avrà avuto maggior contatto. E anche l’altro studio, ugualmente a Francoforte (n. 21) , con Sileno in un paesaggio con due capre – palesemente in sintonia con la tavola della National Gallery con Olimpo e Marsia – è molto più nel carattere di Agostino, che evidentemente adopera anche l’acquerello con penna e inchiostro a quest’epoca. La composizione coll’albero centrale ricorda lo stesso elemento nella Clizia di Cincinnati.

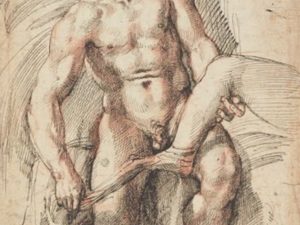

Here attributed to Agostino Carracci Silenas and cupid Frankfurt, Städel Museum

Sempre di più Annibale alla Galleria Farnese si mostra capace di lavorare senza disegni preparatori, o almeno senza le precisazioni di cartoni; non sarebbe stato tipico del suo lavorare fare un disegno così preciso per un elemento decorativo quale gli amorini dello strumento musicale; allo stesso modo il disegno completo per la Tazza, ora al Metropolitan Museum of Art, (n. 22), rappresenta una precisazione eccezionale, realizzata dopo tutta una serie di disegni che il fratello aveva preparato.

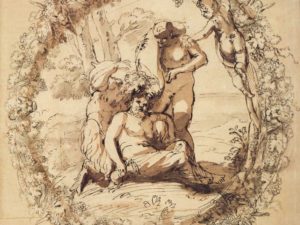

La preparazione della cornice per il pergolato sembra calzante per il contributo di Agostino, e ci può sembrare che questo fosse la sua parte della invenzione: ma egli avrà anche fatto un disegno per l’insieme in concorrenza, che sarà il disegno del British Museum, e lo studio a Chicago (n. 23). Questi hanno come cornice elementi incisivi teste alternate di montone e leone. E’ stato proposto che i tratti di paesaggio e l’acquerello grigio possano essere stati aggiunti da Michel Corneille, ma almeno gli alberi e il paesaggio sembrano tipici di Agostino, vicinissimi agli sfondi delle incisioni delle Lascivie (n. 24). Non vengono inseriti nel disegno finale, che segue la decorazione più corsiva del disegno del Metropolitan colle foglie e viticci più sciolti, e sono solo gli Amori che vengono adoperati nella Tazza stessa. Questi sono legati alle figure che incorniciano lo scudo delle armi Farnese / Aldobrandini che Agostino poté incidere nella primavera del 1600 a Roma, per un Epitelio in celebrazione del matrimonio tra Ranuccio Farnese e Margherita Aldobrandini. (n. 25) Agostino sarà partito da Roma non nel 1599, ma all’approssimarsi del matrimonio stesso a maggio, poiché lo ritroviamo occupato con Ranuccio a Parma nel luglio 1600, mentre l’opera a cui era stato destinato era già in corso da tempo (n. 26). Il cenno dell’Agucchi al fatto che ancor meno della metà della Galleria fosse terminata assume un’ importanza maggiore, perché significa che così era al momento del matrimonio. Ma il progetto di cui abbiamo ragionato è un esempio della collaborazione armoniosa di cui Agucchi parla (n. 27), e i vari disegni di Agostino di Bacco e i contorni decorativi, rendono l’idea del tipo di ricerca che egli intraprese in compagnia di cortigiani come l’Orsini. Il disegno a penna e inchiostro a Windsor, (n. 28) colla testa di Bacco al centro di una ghirlanda d’alloro, e gli schizzi di una tazza piatta, ci danno una idea dei suoi richiami ai modelli classici nelle medaglie e negli intagli antichi, così come lo stesso carattere si vede nel disegno con il capo di Sileno in una nicchia tonda, con una testa di montone (Louvre, Inv. 7192, Loisel 536 – dato ad Annibale).

Un altro disegno dello stesso momento di un Bacco con montone (n.29) che ugualmente richiama ai classici -la figura in piedi di Bacco è caratteristica di varie collezioni romane- è forse collegato al Bacco che porta in mano la tazza uguale a quello che figura nel disegno colla testa di Bacco; la soluzione grafica per le gambe è palesemente di mano del fratello maggiore.

Here attributed to Agostino Carracci Verso Two Cupids Fighting

Recto, Designs for the Farnese Tazza Cleveland Museum of Art

Here attributed to Agostino Carracci Design for the Farnese Tazza The New York Metropolitan Museum of Art

Annibale Carracci Design Farnese for Tazza New York Metropolitan Museum of Art

Agostino Carracci Studies for the Tazza Farnese Windsor, Royal Library

Here Attributed to Agostino Carracci Standing Bacchus Paris, Louvre

La somiglianza tra questa testa di Bacco e quella di Marsia ( ? ) nel clavicembalo non è casuale; si tratta dell’ispirazione che Agostino prendeva dall’antico per dare vita a questa moderna reinterpretazione del mondo antico. Il disegno ricorda anche il quadro di un Bacco in piedi, a Napoli (n. 30), il quale ha un origine Farnese, e che è palesemente di mano di Annibale, contandosi tra le poche opere fuori dalla Galleria che egli avrà lavorato a cavallo del secolo. Queste differenze sono abbastanza facili da distinguere, perché l’approccio e la fattura sono evidenti: è molto più difficile riconoscere le mani diverse in un affresco dove ad certo punto erano sostituibili l’uno per l’altro, e volutamente hanno contribuito ad un prodotto tipico della ditta Carracci. Ma Agostino è salito molto meno sui ponteggi per applicarsi all’affresco, era molto grasso (si diceva che era l’immagine di Sileno stesso) e pativa di asma, come ci dice Mancini, il quale ci parla dei quadri più piccoli che faceva evidentemente per mecenati della corte.

Sul verso del disegno a Chicago di cui al recto il gruppo di Sileno è palesemente di Annibale troviamo una finta medaglia con due putti che si contendono un ramo di palma, evidentemente della stessa mano degli Amori a Francoforte. Il recto del disegno ha come soggetto anche delle idee per il pergolato forzatamente di Agostino, e un cenno per i putti che vi si arrampicano. Invece il disegno (finale?) per l’insieme in penna e acquerello al Metropolitan Museum of Art è manifestamente di Annibale stesso, con una pennellata dei particolari grafici molto più sciolta, il quale riprende alcune delle idee del fratello. La presenza di queste mani diverse in questa serie di disegni, e la presenza dei putti che lottano nel disegno di Chicago dimostra che Agostino era coinvolto nell’invenzione degli Amori che si sfidano, Eros e Anteros, nella Galleria stessa, i quali per Bellori erano la chiave dell’ intera decorazione. E ci porta a considerare che ci sono altri studi per i soggetti della Galleria che sembrano essere di Agostino, mentre la pittura stessa è manifestamente del fratello minore. Mentre Agostino si è dedicato, nell’ultimo decennio della sua vita, a delle invenzioni pittoriche che erano in concorrenza con Annibale, egli stesso – come apprendiamo dalla descrizione di Agucchi – riconosceva la sua superiorità in questo campo, comunque i propri sforzi venivano considerati una minaccia. I due pannelli ai due lati del Trionfo di Bacco saranno stati la goccia che ha fatto traboccare il vaso, perché lanciavano una sfida al monopolio della mano di Annibale, e siccome Agostino era ben visto dai cortigiani del cardinale, si capisce che egli volesse essere considerato non solo per l’ingegno ma anche per la sua bravura da pittore.

Una incisione che enfatizza il tema della Galleria Farnese è l’Omnia vincit amor del 1599. Citata da Bellori come un’opera di Agostino, in età moderna è stata messa in relazione con un’invenzione del fratello più giovane, perché le due ninfe gemelle sono una eco evidente di quelle dipinte nel Paesaggio con Diana e Callisto della collezione del Duca di Sutherland a Mertpoun. Il quadro fa parte di una coppia, di cui l’altra è la Toletta di Venere della Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna. I due quadri sono stati separati al tempo della vendita Orleans nel 1598, e da quel momento sono stati sempre attribuiti a due diverse mani. Ora sembra che il gruppo di figure sia di mano di Albani, che arrivò a Roma dopo la morte di Agostino, mentre, secondo me, il paesaggio è del suo caro amico e collega Giovan Battista Viola, che molto contribuì alla diffusione del paesaggio carraccesco nella Roma del primo Seicento (come meglio argomenterò in una prossima pubblicazione).

Non sembrano esserci ragioni per attribuire le figure della stampa di Agostino a suo fratello: Agostino aveva dipinto il soggetto della stampa, Cupido che domina Pan, sul camino di Palazzo Magnani a Bologna, e il disegno completo di Francoforte regge qualsiasi osservazione che induca a pensare che il disegno sia tutto assegnabile alla sua mano. La storia del dipinto, in ogni modo, dimostra il mito di Annibale anche nella generazione successiva: tutte e due le opere furono esportate in Francia dal pittore Jacques Stella, dove la loro qualità esprimeva il mito dell’invenzione carraccesca che non persuadeva i pittori della generazione del cardinale Mazzarino e di Luigi XIV; la mitologia era stata senza dubbio orientata da Bellori quando riferisce che il dipinto (n. 31) si trovava a Parigi presso l’abate de La Noue. Lo stesso autore conosceva l’erudizione di Agostino – lui era l’autore delle sue invenzioni, le quali investigava con grandissima cura – e la ninfa sulla sinistra nel dipinto Sutherland è evidentemente da mettere in relazione non al disegno di Annibale ma alla ninfa sulla sinistra nell’affresco della Galleria di Glauco e Scilla (il titolo tradizionale di questa scena) che nessuno ha mai associato ad altri che ad Agostino. Conosciamo molto bene la fonte per la coppia saffica, che si trovava nello stesso ambiente delle Tre Grazie nella stampa di Agostino (De Grazia, 1979, n. 183, p. 297) e per gli altri cortigiani che accettano l’oro e sono colpiti e penetrati dai satiri, già visti nei cupidi delle Lascivie, per cui non ci sono motivi di credere che questa tela sia stata disegnata o dipinta da Annibale.

Here attributed to Agostino Carracci Landscape with Diana and Callisto Mertoun, Duke of Sutherland collection

Here Attributed to Francesco Albani and G.B. Viola The toilet of Venus Bologna Pinacoteca

Agostino Carracci Anchises Christchurch Oxford

Guardando i cupidi nelle due parti del disegno di Francoforte, associati con la spinetta Farnese ora alla National Gallery, possiamo notare che il paesaggio di sfondo coincide con quello di Diana and Callisto, per similitudine delle dolci colline sullo fondo e per la presenza degli alberi nelle valli discontinue. Si notano anche citazioni da modelli classici (nel caso del disegno probabilmente i cupidi derivano da un sarcofago romano), come il paesaggio ben inserito e costruito prospetticamente. Qui vediamo Diana a cui sta scivolando via il suo sandalo, esattamente come la Venere nuda di Anchise nella Galleria, un dipinto di cui Agostino fornì il disegno preparatorio (Christ Church, Oxford n. 32 ). Le figure sono contenute, e derivano evidentemente dall’antico, e sono un ricordo del gruppo delle Niobidi scoperto nel 1582 e allestite come un tableau a Villa Medici dal Granduca Ferdinando. Questo gruppo sarebbe stato un’importante fonte di riferimento per i pittori del Seicento, principalmente per Poussin, e sembrerebbe essere all’origine delle compatte fisiognomie classiche adottate da Agostino, e dalla scuola dei Carracci dopo di lui. Il dipinto Mertoun è un esempio della sofistica rappresentazione del paesaggio raggiunta da Agostino alla fine della sua esperienza romana e che fu enormemente importante per i suoi seguaci, principalmente per Domenichino, il principale erede di questo genere e disciplina, che combinò un idioma decorativo in piccola scala con soggetti storici, fornendo un prototipo iconografico che avrebbe avuto gran successo nel corso del Seicento.

Agostino Carracci Omnia Vincit Amor engraving 1599

Agostino Carracci Drawing for the Omnia Vincit Amor Frankfurt, Städel Museum

Ancient statue group of Niobids in the Villa Medici garden (engraving by Perrier)

A differenza delle tele dipinte da Annibale, dove il paesaggio faceva probabilmente parte di una scaffage architettonico più ampio, questo era un cabinet painting con molte allusioni classiche, senza dubbio ottenute grazie agli scambi con Fulvio Orsini. Il disegno ebbe un gran significato per le generazioni di committenti che volevano usare questo paesaggio così duttile da essere usato come sfondo neutro per ogni tipo di storia o per scene morali: è importante capire che questa invenzione iconografica fu parte di alcuni strumenti educativi forniti dall’inclinazione di Agostino alle generazioni successiva. Dal momento che questo disegno può essere messo perfettamente in relazione alla stampa del 1599, eseguita alla fine della carriera romana di Agostino, e il fatto che il pendant era stato completamente eseguito da altre mani, si può dimostrare che questo è stato uno degli ultimi pezzi fatti a Roma, probabilmente proprio per Odoardo Farnese. L’idea che era stata basata su un’invenzione del fratello, dipende dal fatto che la maggior parte delle stampe di Agostino sono state duplicate, dal momento che voleva essere considerato un artista fatto prima di andare a Roma, e che gli scambi, avuti con antiquari come Fulvio Orsini, gli avevano fornito un’ampia gamma di soggetti dall’antico che avrebbe potuto ripetere e usare nei suoi dipinti.

L’incisione di Agostino è il tema centrale del soffitto, tanto che la sua data rappresenta un momento cruciale per l’esecuzione del dipinto della Galleria, e anche se non è necessario ipotizzare che la decorazione ha una narrazione consistente, questa insinuazione finemente sensuale ebbe molto a che fare con il loro successo. Era dopo tutto questo il motivo per cui questo libertino era famoso, se leggiamo bene la sua frase bella pargoletta che ancor non sente amore. (n. 33)

Bellori si mostra prudente nello spiegare la sensualità presente nei cicli di affreschi cinquecenteschi, del resto il mondo di Raffaello e della pittura di maniera non era stato così erotico come quello di Praga al tempo dell’ Imperatore Rodolfo, quindi aveva bisogno di una spiegazione innocente nella fase più riformatrice del Seicento a cui apparteneva. I particolari del paesaggio, che è incredibilmente curato, e di una importanza capitale per la generazione di Domenichino e Viola -di cui il primo era abbastanza indipendente per mettersi in proprio – fanno capire che l’insegnamento di Agostino fu più rilevante rispetto a quello di Annibale, già ora divenuto debole, dopo che era partito da Bologna sei anni prima. E per Agostino il paesaggio era legato alla quadratura, con l’inserimento di figure istoriate per creare un nuovo genere decorativo. Questo è il classicismo formale che l’influenza di Agostino ha cercato di imporre, e man mano che si fidava maggiormente delle sue capacità inventive cercava di inserirlo nel contenuto delle scene e non solo nella loro disposizione generale.

Non c’è quindi più motivo di attribuire ad Annibale tanto l’invenzione quanto l’esecuzione di questo capolavoro di Diana e Callisto che è stato da sempre molto ammirato (e considerato interpretazione in vena classica del quadro di Tiziano dello stesso soggetto, che sino a poco tempo fa era nella stessa collezione). Ma questo è stato valutato poco nei recenti studi su Annibale (vedi Robertson e Benati n.34) mentre invece sarebbe lecito considerarlo il capostipite di quel classicismo compatto che Agostino ebbe sviluppato a Roma, completo dei dettagli di quel tipo di paesaggio che i suoi successori, Domenichino, Grimaldi e Poussin hanno tanto apprezzato. Esso prende il posto che, in tempi moderni, ha goduto la famosa Fuga in Egitto della Doria Pamphili, opera anch’essa tappa maestra di questo paesaggio ‘classico’, ma eseguita da Domenichino, come abbiamo già argomentato. La tradizione paesaggistica carraccesca va ricondotta ai modelli e agli insegnamenti di Agostino e anche quando ci sono pochi esempi di quadri (ma allo stesso tempo di più di quelli attribuiti al fratello), i suoi disegni mostrano che egli era l’inventore di composizioni che si prestavano ad essere variate e moltiplicate. La gamma di elementi presenti nella Diana e Callisto hanno loro origine in tutta una serie di disegni e quadri che erano beni noti alla nuova generazione di pittori bolognesi a Roma, che rappresentano una fonte di gran lunga più importante che non le opere del pittore che è sopravvissuto come il rappresentante di tutto quello che il nome Carracci comportava, che aveva un modo molto più sciolto in questo genere. Queste forme fornivano non solo nuovi modelli per le vignette che i ‘pittori doratori’ realizzavano per tutto il secolo precedente, alternate con grottesche nelle decorazioni delle pareti, ma davano uno sfondo articolato e naturalistico ai soggetti amati dai mecenati, cui si era risvegliata la passione per le storie del mondo antico. Il quadro a Mertoun è un esempio chiave della sofisticazione della composizione paesaggistica di Agostino alla fine del soggiorno Romano, tanto importante per Domenichino, erede principale di questa disciplina che abbinava un genere decorativo con soggetti di storia su una scala ridotta, una combinazione che avrà grande successo nel Seicento.

I disegni che possono essere collegati a queste pitture sono pochi, ma in verità più di quanto si possa ricondurre alla partecipazione di Annibale nel genere. Una considerazione generale è che questi studi sono raramente connessi ad elementi di un paesaggio dipinto, anche perché questo sembra essere un genere in cui si praticava una invenzione libera. Malgrado l’elogio di Luca Faberio per gli studenti dell’Accademia degli Incamminati che disegnavano ‘alla villa’, sembrano pochi i richiami alle caratteristiche paesaggistiche davvero ‘naturali’, ma per altro verso questo vuol dire che il carattere del disegno è abbastanza personale tanto da rendersi riconoscibile, e nei disegni di Agostino esiste un filo più consistente che non in quelli di suo fratello. E probabile che la maggior parte di questi disegni abbiano ricevuto la loro attribuzione a causa delle bevi menzioni di questa attività nelle biografie più antiche, seguendo lo stesso principio di quadri della scuola carraccesca.

Here attributed to Agostino Carracci Landscape with Nymphs and goats bucking Paris, Louvre

L’assenza di esemplari di paesaggi di paternità annibalesca non ha impedito a Bellori e ad altri promotori dell’arte dei Carracci di esportare dipinti e disegni che erano solo generalmente carracceschi, coll’attribuzione ad Annibale stesso. Agostino era meno fiducioso per la sua pittura, ma paradossalmente era un disegnatore e insegnante molto attento, che seguiva un percorso grafico preciso nel cercare di sviluppare le sue composizioni che risultano spesso molto più finite, affermate e organizzate. Uno dei primi nel catalogo della Loisel, un disegno che appartenne a Mariette con una ninfa che indica col dito (Louvre Inv. 7121, Loisel n. 325 ) (n. 35) , ha delle figure che richiamano il gesto di Diana , ma anche la schiena callipigia della ninfa a destra nella tavola a Bruxelles di Diana e Atteone. Lo scontro delle capre si ripete in vari altri disegni, compresi quelli a Stoccolma e Windsor, che mostrano la ricerca che il pittore faceva per trovare una soluzione a questa raffigurazione nel soffitto Farnese; allo stesso modo dei disegni di Europa che cavalca all’ amazzone per il piccolo quadro già Farnese, e della Galatea del soffitto al Palazzo del Giardino. Ora, che ad Agostino venga riconosciuto non solo il quadro della Fête Champêtre a Marsiglia, ma anche il disegno del Louvre, è diventato più ovvio riconoscendo la sua personale grafia nei tronchi degli alberi, gli stessi che abbiamo visto nel disegno a Francoforte per Omnia vincit Amor.

Agostino Carracci Fan with head of Diana

(Detail) Landscape with two Satyrs and Nymphs

Questa incisione e anche molto vicino al carattere di quella del Ventaglio, il quale nondimeno è stato collegato, senza valido motivo, colle celebrazioni per il matrimonio di Ferdinando de’ Medici e Cristina di Lorena nel 1589. Mi sembra verosimile avvicinarlo ad un evento del genere, e ora che sappiamo che Agostino era ancora presente a Roma per l’unione tra gli Aldobrandini e i Farnese, l’epitelio che egli ha inciso per il matrimonio del 7 maggio 1600, è probabile associarlo a un elemento effimero per quell’occasione. Il piccolo paesaggio ovale è vicino a quello dell’incisione di Omnia vincit Amor, quanto anche a quelli delle Lascivie (e anche ai disegni per la Tazza Farnese), e i due satiri che osservano la ninfa bagnante sono altrettanto simili a quei satiri del disegno preparatorio per l’incisione del 1599 a Francoforte. Risulta invece che la poesia di cui la prima riga figura nel disegno per il Ventaglio (formerly Paul Oppé collection, sold Sotheby 5 July 2016, Lot 48) , Inghilterra (n.36) è tratta da uno dei Madrigali di Michelangelo (Madrigali, LXI) che inizia Mentre i begli occhi giri, Donna… e continua colla lode della amata ‘Che’n sì begli occhi io mi veggia sì brutto / Tu ne’ miei brutti ti veglia sì bella’. La poesia di Michelangelo non venne pubblicata (dal nipote Lionardo) sino al 1623, ma e chiaro che i versi circolavano tra gli amatori, ed è caratteristico di Agostino esserne sempre informato. Infine, la testa di Diana al centro del Ventaglio richiama quella della stessa dea nel Paesaggio con Diana e Callisto che sarà del medesimo periodo, come pure le teste delle ninfe della incisione del 1599.

Attributed to Agostino Carracci Title page of Epithelium 1600 (detail on right)

(Detail)

Ci sono altri paesaggi che Agostino ha dipinto prima di partire da Roma, ma non sorprende che ci siano giunti senza l’attribuzione a lui.

Here Attributed to Agostino Carracci Landscape with Sylvia and Satyr

Here attributed to Agostino Carracci Landscape with a Nymph and Satyr Paris, Louvre

Molto vicino al carattere della Diana e Callisto è il Paesaggio con Silvia e il Satiro a Bologna, Pinacoteca Nazionale (n. 37) A lungo ammirato come opera di Domenichino, se ne conosce la storia solo dal primo Ottocento. Il fogliame ben definito a sinistra fa risaltare la prospettiva lontana, con Silvia inseguita da un satiro nei piani più distanti: nel gruppo in secondo piano la vediamo rapita allo stesso modo del disegno al Louvre (Inv. 7456, Loisel 370) (38) dove troviamo una delle ninfe in primo piano, una di quelle belle delle Lascivie, vista di schiena, in una posa che ricorda quella dell’ Ermafrodito.

C’è un satiro dietro l’albero che dà una sbirciatina, al modo di quelli del Ventaglio o quelli delle Lascivie, in una prospettiva strutturata con piccole figure a distanze misurate. Agostino aveva inciso i disegni di Bernardo Castello per l’edizione del 1590 della Gerusalemme liberata del Tasso, ma qui la scelta di fonte letteraria è insolita. I particolari del paesaggio, come anche le figure, sono strettamente vicini ad altri esempi di questo gruppo ristretto di tele, e notiamo le stesse armi da caccia poggiate contro l’albero a sinistra. Il soggetto è preso dall’Aminta del Tasso, un romanzo pastorale ambientato nel mondo classico ai tempi di Alessandro Magno e pubblicato in prima edizione nel 1573, e Agostino adopera le stesse disposizioni per inquadrare il soggetto nell’ambiente, con la ninfa Silvia che vive nei boschi e viene corteggiata e alla fine conquistata dal pastore Aminta, nonostante che si fosse votata alla castità in onore della dea Diana. I protagonisti sono posti in primo piano, bilanciati a sinistra dalle armi della caccia – quelle stesse della Diana e Callisto – e anche con gli stessi cani vivaci, mai così reali quanto quelli di Annibale. Queste ninfe sono varianti di quelle della mitologia della Galleria stessa, ed è naturale che quelle delle Lascivie siano dello stesso momento. Gli alberi e il fogliame hanno un carattere particolare, e sono simili a quelli che si ritrovano nei disegni, come vedremo. La soluzione grafica dell’ albero a sinistra che fa da cornice alla vista è una versione colorata del fogliame nei disegni, come quello di un soggetto mitologico, Salmace ed Ermafrodioe al Louvre (Inv. 7492, Loisel n. 742 ) (n. 39).

Here attributed to Agostino Carracci Landscape with Salmacis and Hermaphroditus Paris, Louvre

Here Attributed to Agostino CarracciLandscape with a boatman Paris, Louvre

Agostino qui ha riempito tutta la pagina con questo studio, ove gli attori sono inseriti dentro i particolari del paesaggio: Ermafrodito sorge dall’acqua che simboleggia la sua unione colla ninfa della fonte Salmace, la quale è mezza nascosta dietro il tronco dell’albero. Un altro disegno con molte caratteristiche grafiche in comune è lo Studio con barcaiolo (Inv. 7458, Loisel 759 – ‘atelier d’Annibale Carrache’) (n. 40) con gli stessi tronchi d’albero e rami che abbiamo incontrato nei quadri. Lo sforzo che fa il barcaiolo nella spinta sul remo è un modo di comunicare il senso di energia e di movimento che sarà proprio una delle ricerche che farà il Domenichino, mentre la posizione del personaggio che appoggia sul gomito riflette quella stessa posa statuaria adottata dalla ninfa che appende l’abito sul tronco dell’ albero a destra della Diana e Callisto. I tre disegni del Louvre (Inv. 7458, 7492, 7121) condividono le stesse caratteristiche nell’associare le figure mitologiche in primo piano, con casupole rustiche e anche tizianesche nello sfondo, e rappresentano una delle basi del paesaggio classico come si svilupperà a Roma durante il ventennio successivo.

La paternità di Agostino è stata riconosciuta anche ad un altro paesaggio su una scala simile a Silvia e il Satiro di Bologna, cioè quello con Europa e il toro che Carel van Tuyll ha individuato come quello descritto nell’ inventario del 1662 dei quadri dal ‘primo camerino accanto la Morte’ di Palazzetto Farnese, per Agostino.

Agostino Carracci Europa and the Bull London, Private collection

Agostino Carracci Andromeda Engraving

Mentre l’inventario precedente del 1653 lo descrive come di Annibale, quello ancora prima del 1649 lo cita come ‘la favola d’Europa e due tritoni’ e la presenza di due disegni di mano d’Agostino sembra convincente per riconoscervi il quadro in origine nel Palazzetto, come Carel van Tuyll argomentò nel 1986 (n.41) La Europa ha la stessa posa della Andromeda dell’ incisione di Agostino, una posa intermedia verso quella della Galatea o Teti dell’ affresco al Palazzo del Giardino. Con gli amori e i delfini è vicina con quelli dell’ affresco con Glauco e Scylla/Venere e Tritone della Galleria, ma anche con quelli delle scene di Parma. Gli amorini in aria sono quelli della Galleria, che poi saranno imitati anche ripetutamente in vari paesaggi da G.B. Viola, il quale lavorò accanto a Agostino a Bologna prima di arrivare a Roma in compagnia dell’Albani. C’è anche la presenza di varie figurine a scala secondo le distanze, elemento di un altro gruppo di paesaggi carracceschi, una considerazione che ci riporta all’insegnamento che il fratello maggiore ha esercitato in questo genere paesaggistico. Il Van Tuyll ha giustamente osservato la vicinanza stilistica che presenta questo paesaggio con un altro paesaggio di Agostino, il Paesaggio con bagnanti della Galleria di palazzo Pitti, a Firenze, di un momento anteriore ma sempre con elementi che lo avvicinano al quadro di Abbondanza e Felicità. Ma la composizione dell’Europa che cavalca il toro ricorda anche il medaglione della Galleria Farnese, con il quale condivide più aspetti, ed è probabile che anche questo sia di paternità agostiniana, con i suoi accenni a Tiziano. Lasciando da parte la considerazione di chi fu l’esecutore materiale dell’affresco, riconosciamo quanto Agostino torni ripetutamente su questa posizione alla amazzone, come ad esempio nella Teti a Parma, e nei numerosi disegni preparatori.

Here attributed to Agostino Carracci Diana and Actaeon Musée des Beaux-Arts, Brussels

Un’ altro dei quadri Farnese che deve essere di mano di Agostino è la piccola tavola con Diana e Atteone a Bruxelles. Sebbene questo quadretto, che appartenne a Luciano Bonaparte prima del suo arrivo al Musée des Beaux-Arts di Bruxelles, sia di solito riferito ad Annibale, diventa sempre più evidente come invece sia un altro esempio della conversione personale di Agostino verso i temi dall’antico da lui visti a Roma, in particolare i marmi di Palazzo Farnese. La schiena della ninfa a destra è un’eco meravigliosa di quella Venere Callipigia che era un acquisto recente a Palazzo Farnese, ripresa anche nel piccolo affresco con Diana e Callisto sulla parete della Galleria, e anche nella Caccia di Diana che Domenichino avrebbe dipinto in seguito, e che dovette cedere al Cardinale Scipione Borghese. Ma i quadretti sono versioni più modeste di questi temi classici, riflesso di quella passione per l’antico che è presente nella Galleria; la lancia e la faretra di Diana appoggiate al bordo del laghetto sono gli stessi anche nella Diana e Callisto a Mertoun, ed ancora nel paesaggio con Silvia e il Satiro a Bologna. Questi quadri di Palazzo Farnese erano di primaria importanza per i seguaci di Agostino, anche perché potevano servire per la rappresentazione degli stessi temi con varianti quando finalmente sarebbero state terminate le pareti della Galleria.

A Napoli il Paesaggio con la visione di Sant’Eustachio ha molti ammiratori, ma non sempre la conferma che si tratti di opera di Annibale. Il quadro giunse a Capodimonte con gli altri quadri Farnese (dapprima inventariato come di Annibale, nell’inventario del 1644 di palazzo Farnese, nel 4º camerino del Palazzo principale, e poi nell’inventario del 1662 quando giunse a Parma (Jestaz, 1994 Inv. 3226, p. 132) e sembra probabile che sia un quadro eseguito per Odoardo Farnese, forse al momento in cui veniva nominato titolare della chiesa di Sant’ Eustachio nel 1595. Il cavallo posto ad angolo obliquo rende efficacemente la prospettiva della scena, e lo sfondo paesaggistico è volutamente differente rispetto agli artifici dei pittori olandesi che lavoravano in concorrenza, cercando di comunicare una natura remota e estranea, mentre i bolognesi cercavano di proporre uno sfondo selvaggio ma conosciuto. Mentre la Ann Sutherland Harris ha proposto che i due famosi paesaggi del Louvre, La Chasse e La Pêche, regalati da parte di Camillo Pamphili nel 1665, potrebbero anche essere di mano di Agostino, a parer mio queste esercitazioni così libere rappresentano un genere di facile padronanza del fratello più giovane. E lo studio del cane (Uffizi, Inv. 12418) che è così vicino al profilo di quello in primo piano della Chasse, è stato anche talvolta erroneamente ricondotto all’animale in primo piano alla Visione di Sant’Eustachio. I cani più eleganti di Agostino sono un elemento particolare, e anche quando i disegni potevano essere condivisi dallo studio intero (al punto che l’autore potrebbe essere diverso da quello che lo dipinge nella tela) sembrano possedere un’altro aspetto, un carattere più araldico che non è tipico di Annibale. Il quadro a Napoli viene sempre di più omesso dalle attribuzioni ad Annibale (per esempio nella recente monografia di Clare Robertson), e rende soddisfazione concludere che appartenga a questo gruppo ristretto di opere. Ma l’aspetto più convincente dell’attribuzione sta nella considerazione dell’ordine e della prospettiva adoperati, elementi che si ritrovano anche nei disegni di Agostino, come vedremo.

Here attributed to Agostino Carracci Landscape with Sacrifice of Isaac Paris, Louvre

Considerando i dipinti con figure piccole e paesaggi possiamo anche restituire alla paternità di Agostino un’altro quadretto che è riferito ad Annibale dal momento che il banchiere Everard Jabach lo vendette con il compagno a Luigi XIV nel 1671. Il re Luigi, al pari di tanti francesi della sua generazione, era pieno di entusiasmo per i Carracci, e venne ingannato da diversi cortigiani e amici nell’acquisto di opere bolognesi, particolarmente dipinti su rame. Ventidue opere di Annibale sono elencate nel catalogo ragionato della collezione reale redatto da Bernard Lepicié nel 1754, ma è evidente che molti di essi erano opere bolognesi di altre mani, come il piccolo Concert sur l’eau che il Re comprò da Richelieu ad un prezzo altissimo, come opera originale di Annibale, o i tre quadri provenienti dal Cardinal Sannesi di cui Bellori ha parlato splendidamente ma che risultano essere di mano di giovani seguaci del grande maestro. Jabach è anche noto per aver fatto fare delle copie di molti disegni carracceschi della sua collezione, che poi ha sostituto agli originali nel venderli al Re.

Il Paesaggio con il sacrificio di Isacco era largamente ignorato fino alla mostra dei Carracci a Bologna nel 1956, quando invece venne individuato come esemplare del contributo al nuovo linguaggio classico paesaggistico da parte di Annibale. Veniva considerato differente rispetto al compagno, la Morte di Assolonne, opera per la quale invece esistono vari disegni di scuola carraccesca. Ora è acclarato che il Sacrifico d’Isacco sia un’opera di Agostino databile verso la fine del suo soggiorno romano, mentre il pendant di Assolonne sia opera di Viola (forse vicino all’Albani che fu suo compagno per molti anni) il quale non era tanto bravo come figurista, e prossimo al disegno di Agostino con la Morte di Giuda, cui abbiamo già accennato. Il fogliame del Sacrificio è dipinto chiaramente nella stessa grafia di quello della Diana e Callisto e della Silvia e il Satiro, e anche per il fatto che siano caratteristiche ancora manierate possiamo essere sicuri di riconoscerne la comune paternità. Le figure piccole in lontananza sono dello stesso carattere di quelle di Agostino nelle incisioni delle Lascivie, e non sorprende che il figlio Antonio Carracci continui a dipingere angeli nella stessa logica. Agostino era molto preso dalle soluzioni di prospettiva per quanto riguarda il paesaggio, e ci sono vari esempi di figurine nello sfondo (come in uno dei disegni per la Abbondanza e Felicità) poste per misurare le distanze. Questo effettivamente sarà stato un elemento dell’ insegnamento di Agostino, e quando queste figurine abbozzate sono presenti nei disegni carracceschi si tratta di solito di un ricordo della sua insistenza per comunicare le distanze su una scala misurata. Malvasia parla di questo I, 1841 p. 277, 347) e anche dei suoi scritti sulla prospettiva che risultano evidentemente importanti per gli Incamminati. In confronto, l’intendimento di Annibale riguardo alle distanze era, possiamo dire, più dovuto ad un intendimento intuitivo; egli non aveva bisogno di regole o misurazioni, ed era sempre molto più coinvolto nella rappresentazione naturalistica di forme umane viste da vicino.

Molto di quello che abbiamo detto delle opere di Agostino a Roma riguarda commissioni evidentemente eseguite per il cardinale e per personalità che erano di casa al palazzo, egli infatti godeva di un’amicizia con i cortigiani ben diversa dal rapporto che invece ebbe suo fratello, sempre timido e riservato, anche quando si lasciava distrarre dai soggetti in cui s’imbatteva ‘not a catt or animal about his howse wch Annibal and ye Caraccios did not disegne with pen’ (‘non c’era gatto o animale attorno la casa che Annibale e i Carracci non disegnavano a penna’, come ci ricorda Richard Symonds n. 42) oppure anche da domestici di sua conoscenza, perché era apprensivo fuori della sua cerchia sociale.

Sembra possibile che fosse lui il candidato naturale per la commissione della pala d’altare con il ritratto di Odoardo, eseguita per la cappella della famiglia Farnese a Camaldoli, e ora a Firenze alla Galleria Pitti. (n. 43). In seguito al riconoscimento da parte di Carel van Tuyll dei disegni per gli affreschi del Palazzo del Giardino, (n. 44) è diventato più facile riconoscere lo stesso autore nel disegno (su ambo i lati n. 45) con una rappresentazione inconfondibile di Sant’ Ermenegildo e sul recto un altro per una delle cariatidi della Galleria. Poche citazioni, nello stesso tempo, per il piccolo tabernacolo a Palazzo Barberini (sebbene rechi gli stessi santi sulle ante dell’altarolo), un oggetto caro al cardinale Odoardo perché lo menziona esplicitamente nel suo testamento legandolo alla cognata, Margherita Aldobrandini. Sembra verosimile attribuirlo ad Antonio, il figlio naturale di Agostino, come ho già avuto modo di proporre; la sua lealtà e direzione stilistica erano certamente guidate dalle lezione che ebbe dal padre.

Questi quadri sono sempre stati nel passato considerati come aspetti della grande versatilità che si è voluto individuare in Annibale, e ancorché rimanga ancora difficile marcare il confine tra i due fratelli, è possibile intravedere la consistenza dell’approccio di Agostino, sia per la sua cura per le invenzioni, sia per la sua preparazione nel governare il lavoro di un grande studio. La prima parte della sua carriera è segnata dalla sua attenzione alla varietà di stili e scuole, come dimostrano le molte incisioni riproduttive, ma gli capitò anche di essere il manager dello studio della famiglia, e di disporre i soggetti e la quadratura delle decorazioni che questa impresa aveva da realizzare. Torneremo su alcuni dipinti di paesaggio considerando i suoi disegni di questo soggetto, attraverso i quali è possibile di rintracciare un percorso evolutivo per il fatto che la sua grafia è alquanto personale; in confronto a quelli del fratello sembra sempre che ci sia un pensiero per l’insieme. La conseguenza degli anni passati nell’osservare e riprodurre le opere altrui lo portò ad una maggior competenza nella composizione, contrariamente alla sua disponibilità iniziale a restare in secondo piano quando si trattava di dipingere a colori. Anche se non smise di gestire l’impresa, il suo ultimo decennio è caratterizzato dalla dedizione ai disegni originali. Proprio questo è il cuore della svolta classica che l’impresa dei Carracci adottò a cavallo del secolo, e in particolare nell’epicentro di questi interessi che era il Palazzo Farnese e la sua collezione di marmi antichi. Non dobbiamo pensare che per le sue assenze a causa dei viaggi non fosse una forza continuamente presente, sia nel potenziare la incredibile energia creativa del fratello, sia per condurli in una direzione accademica di cui era principalmente responsabile. La virtuosità della mano di Annibale fu irresistibile per tutti i collezionisti, ma la fantasia nel ricreare dalla mitologia antica che a Roma venne maggiormente individuata nel fratello maggiore costituisce l’eredità più duratura della loro collaborazione.

di Clovis Whitfield London luglio 2017

NOTE

19 R. Zapperi, in ‘Annibale Carracci e Odoardo Farnese’ Bollettino d’Arte, 2010/2012, 8, p. 82, underlines this role of the Spanish courtier, who is identified by Bellori (1976, p.78); Zapperi connects him with the Juan de Rosas who is recorded in the Farnese account books. Zapperi supposes that the Tazza must have been bequeathed to Odoardo on the courtier’s death (1619) as happened with other members of his circle.

20 A.S. Harris, 2000

21 Pace A S Harris, in her review of the Washington Drawings of Annibale Carracci show, in Master Drawings, Vol. XLIII, 4, 2005, p. 518/20, who regards it as Annibale. Agostino Carracci Two cupids picking grapes Frankfurt, Städel Museum

22 Washington DC, 1999/2000, No. 67

23 The Drawings of Annibale Carracci, Washington, DC, 1999/2000, No. 66. Both have usually been attributed to Annibale, although Byam Shaw (Drawings by the Carracci and other Masters. Colnaghi, 1955) already saw them as by Agostino., and he also regarded the wrestling Cupids on the verso of the Chicago drawing as Agostino, for which see below.

24 A complication is Villamena’s concurrent design for the Paniere, which includes the central group of the satyrs refreshing the recumbent Silenus, but with the satyr holding the shepherd’s crook on the left side of the design. An anonymous print with a landscape background must reproduce an alternative Agostino composition with the his cupids leaning over he group from tree trunks either side (as in the Orsini spinet) while the landscape perspective behind and sky are characteristic, although the print itself is anonymous (it may possibly be by Villamena)

25 Published recently by Stefano Colonna, “ Due incisioni inediti di Agostino Carracci per gli epitalami di

Ranuccio Farnese e Margherita Aldobrandini e il programma della Galleria Farnese’ En blanc et noir, Studi in onore di Silvana Macchioni, Roma Campisano 2007; and in his La Galleria dei Carracci in Palazzo Farnese, Gangemi, Rome 2007, p. 75 – 80.

26 The stucco including the figure groups of the Loves of Jupiter (Semele, Leda, Diana and Europa) were in

progress earlier in the year, because Giovanni Bosco was paid for them in April and December 1600: see J.

Anderson, ‘The Sala di Agostino Carracci in the Palazzo del Giardino, Parma, Art Bulletin, 1970, p. 45.

27 In D. Mahnon, Studies in Seicento Art and Theory,, 1947, p. 255.

28 Inv. 1986, Wittkower No. 100, Ashmolean/London 1996/97, No. 47

29 Louvre, Inv 7282, Loisel No. 537 (‘Annibale Carracci’, but recognising its ‘mannerist’ character she associates with Agostino)

30 See most recently, A. Brogi’s catalogue entry in the exh. cat., Annibale Carracci, Bologna/Rome, 2006, No. V.2, p. 238, there dated to 1590/91. As Brogi says, there are few points of comparison in the Roman years, but it still seems more likely this ‘Venetian’ style is the product of a choice made around the end of the decade, as Gian Carlo Cavalli maintained in the 1956 Carracci exhibition catalogue (p. 193).

31 1672, p. 86

32 Drawings of the Carracci from British Collections, 1996/97 no. 46. The drawing, even more suggestive than the painting itself, ‘is executed in Agostino’s characteristically energetic pen style’ (C. Whistler), and has led to some queries about the extent of his contribution to the painting of this scene in the Galleria.

33 From the poem on the verso of Louvre Inv. 7120; see also G. Perini (ed) Gli scritti dei Carracci, Bologna, 1990, p. 173.

34 Not referred to in Clare Robertson’s recent monograph, and set aside by Benati in the Bologna / Rome 2006 – 2007 exh. cat., p. 424, nor in recent studies by Ginzburg, Salomon.

35 The drawing is still laid down. Loisel associates the style of the landscape with that of the drawing, also in the Louvre, of St Francis of Quito (Inv. 7977, Loisel no. 237) which was done by Agostino for a publication printed in Rome in 1587; but it is probably from the turn of the century in Rome.

36 De Grazia Fig. 193a: see also A S Harris in L’Idea del Bello, exh. cat., Rome, 2000, p. 223/24.

37 Canvas, 38,5 by 51,5 cm; Domenichino show, Palazzo Venezia, 1996, No. 28. The painting belonged to Sir Thomas Baring but its history does not extend back beyond the 19th century; it may be the painting sold at Christie’s March 2, 1804, No. 54, said to have come from Rome; it was exhibited at the British Institution 1n 1816 (No. 42) as by Annibale.

38 Listed among the Agostino drawings by Loisel, who however considers it a copy of a drawing at the Victoria and Albert Museum (D-1005 1800) which came from the Croat collection ‘qui semble un original d’Agostino, dans le gout venetien’ . I believe the Louvre drawing, which came to the Royal collection in 1671 from Jabach, is the original.

39 Although Loisel in her 2004 calalogue gives this to Annibale, mainly on the basis of the drawing of a Pieta

recently revealed on the verso, it seems as though this side of the drawing, which is in a quite different hand from that of the recto, is characteristic of the hand of Agostino’s son Antonio. Annibale’s late Pietas were repeatedly used by the faithful pupils, and as his nephew Antonio was in a privileged position with regard to the studies in the studio, particularly perhaps with the drawings left by his late father.

40 Like the Louvre drawing with Salmacis and Hermaphroditus, this drawing has sketches by another hand on the verso; in this case Antonio Carracci is named in a ? practice address, and this probably again is the result of his access to the studio from 1600 onwards.

41 C. van Tuyll, ‘Quadri carracceschi dalla collezione Farnese, in Les Carrache et les decors profanes, Ecole française de Rome, 1988, p. 51-55.

42 A. Brookes, ‘Richard Symonds’s Account of his Visit to Rome in 1649-1651’, in Walpole Society, LXIX, 2007, p. 100.

43 See Annibale Carracci, Bologna / Rome 2006, No. VII. 26, p. 350.

44 C. van Tuyll, ‘Quadri carracceschi della collezione Farnese’ in Les Carrache et les decors profanes 1986 [1988], p. 60/63

45 S. Ginzburg, Annibale Carracci a Roma, 2000, fig 57/58

46 In ‘Antonio Carracci’, Studi di storia dell’ arte in onore di Denis Mahon, Milan, 2000, p. 132-152.

Original English Text

The cupids that Agostino did in Parma are also reminiscent of others from Rome, and of course the most celebrated are those pairs of Eros and Anteros in the corners of the Galleria.These wrestling boys were for Bellori the key to whole subject-matter of the decoration at Palazzo Farnese,and it could be argued that it was Annibale’s subjective originality that arrived at this childish celebration of a political alliance sealed with more than a kiss. Whether or not Odoardo Farnese had in mind his brother’s nuptials (May 7 1600) when he commissioned the decoration with the loves of the gods, the choice of witty learning and incredible pictorial imagination was incredibly serendipitous, not least because it captured the best of two minds in a production that was the swansong of both brothers’ talents, so melded together that it is still almost impossible to decide who did what. It was a miraculous collaboration, and gives the impression that they came together in a way that neither could properly work without the other. But this is for earlier, as it were, since in this essay we are to look at the last first, and the first last, like the parable of the workers in the vineyard. The theme of the cupids is closer to the surface, for there are several even after those of the Galleria. Among the decorative projects both brothers were involved in are the Tazza Farnese and the pictorial decoration of the spinet parts of which are now in the National Gallery, and these are linked by these young boys picking grapes for Silenus, who are variations on the same theme of Eros and Anteros. The Tazza and the Paniere Farnese were what might easily have been ephemeral table ornaments, and we could think only because Odoardo Farnese had these amazingly versatile painters at his beck and call could they be called upon to not only design but actually create these pieces of table silver, and paint the case of a spinet that has long ago ceased to sound, but which continues to intrigue. But neither the Tazza nor the spinet were actually commissioned by the Cardinal, the spinet was decorated for Fulvio Orsini, while the silver was done for a Spanish courtier at the Palazzo. Actually it was reasonably easy to see why Agostino would have been called upon to work in silver, since he was the finest engraver of his day, and he was sharing this task with another engraver, Francesco Villamena from Assisi, who was to engrave the so-called Farnese breadbasket. And the Tazza was a project done for the most insufferable of the courtiers who plagued Annibale’s life through his brother Agostino. This was Don Juan de Rosas, a favourite of the Cardinal’s, who is referred by Malvasia as Don Giovanni di Castro Spagnuolo, notorious for handing to Annibale in another sottocoppa the miserly 500 scudi that he reckoned was owing to him after calculating the artist’s board and lodging over many years, as payment for the Farnese Gallery 19 Although the silver Tazza itself, now reduced to a flat disk, is always referred to as by Annibale, there must be a serious query over whether the actual engraving was done by him or by Agostino, and the extent of the latter’s collaboration. Most of the drawings associated with the project have been traditionally attributed to his brother, but it is obvious that some of them are not, and it is a project that reveals the extent of their collaboration. Some are more involved with the ornament and the boys picking grapes, others are designs for the figures. And as it happens the cupids climbing the circular arbor around the group of Silenus being refreshed with a wineskin in the Tazza are the same children climbing the vines in the spinet cover (National Gallery, London) a commission for another Farnese retainer. The drawing for these figures, illustrated on the cover of the catalogue of the exhibition devoted to drawings by Annibale Carracci in Washington in 1999/2000, has recently been singled out20 as a signal instance of Agostino’s hand, with all of his intensive crosshatching and design motivated by the freedom of the pen. This drawing, now in Frankfurt, was evidently split in two so that the design could be more easily transferred to the instrument case itself, and later patched together with the landscape that now serves as their background. With the hindsight of the figure paintings from Parma, it is easy to see that the actual painting of the spinet was done not by Annibale, but by his brother, who had, we know, a reputation for doing paintings on a small scale, and Fulvio Orsini was the antiquarian at Palazzo Farnese with whom he had most contact. And even the study, also in Frankfurt 21, for Silenus in an landscape with two goats, clearly related to the National Gallery spinet panel with ?Olympus and Marsyas is also in character with Agostino, who evidently used wash as well as the pen at this stage. The design with the central tree recalls the same motif in the Cincinnati Clytie. Increasingly in the Farnese Gallery Annibale seems to have been confident enough to work without fully working out the design on paper, or at least without precise cartoons; it would have been out of character for him to make a precise study for such a decorative element as the boys of the musical instrument, so the complete drawing for the Tazza (Metropolitan Museum of Art22 ) is an exceptional work, done after his brother had done a whole range of studies for it. It as evidently in character for Agostino to create the framing designs for the arbor, and we get the feeling that was his perceived role; but Agostino does appear to have made up a competing design for the whole, represented by the drawing in the British Museum and the study in Chicago23.

Both have the more incisive framing elements punctuated by the alternating ram’s head and lion masks. It has been suggested (AS Harris, review of the Washington DC Exh., Master Drawings 2005 XLIII No. 4) that the landscape elements and the grey wash in the Chicago study may be additions by Michel Corneille, but at least the trees and landscape parts are characteristic of Agostino’s invention, as in the backgrounds of the Lascivie24. They were not used in the final design, which followed the more fluid decoration of the drawing in the Metropolitan with its looser leaves and tendrils, and it was just the cupids who were adopted for the Tazza itself. These cupids are closely related to the supporting figures on either side of the Farnese / Aldobrandini arms that Agostino engraved in the spring of 1600, in Rome, for an epithelium in celebration of the the wedding of Ranuccio Farnese and Margherita Aldobrandini25 . The elder brother must have left Rome finally not in 1599, but around the time of the wedding in May, for he was in Ranuccio’s employment in Parma in July 1600, although the project there was evidently started earlier.26 . Agucchi’s reference 27 to the Galleria being less than half finished at the time of his departure assumes greater significance as this is evidently around the moment of the wedding. But this project is the kind of harmonious collaboration that Agucchi refers to, and Agostino’s numerous drawings with antique references to Bacchus and ornamental surrounds give an idea of the kind of research that he undertook with the aid of courtiers like Orsini. The pen and ink drawing at Windsor28 with the head of Bacchus at the centre of a foliate wreath, and studies of a flat tazza, give an idea of his dependence on classical models in coins and intaglio, as does the study with the Head of Silenus in a tondo niche, with a ram’s head (Louvre, Inv 7192, Loisel 536 (as by Annibale).

Another contemporary drawing of the standing Bacchus with a Ram29, equally with a classical origin as the standing Bacchus was a commonplace in various Roman collections of the Antique, may be is related as Bacchus holds the same flat tazza that is featured in the sheet with Bacchus’s head; the graphic solution for the legs is quite obviously by the elder brother. The similarity between the head of this Bacchus and the head of ? Marsyas in the National Gallery spinet cover of ? Olympus and Marsyas is not accidental: it is Agostino’s close inspiration from the antique in both that powers this modern interpretation of classical figures. The drawing also echoes the painting of the standing Bacchus in Naples30, which has a Farnese provenance and is equally obviously by Annibale, one of the few paintings outside the Farnese Gallery that he worked on at the turn of the century. These distinctions are relatively easy to discern, because the differences of approach and handling do stand out sufficiently; it is much less easy to distinguish their separate hands in the context of a fresco design where they were to some extent interchangeable, and deliberately so as they produced a product that was representative of the Carracci firm. But Agostino worked less frequently than his brother on the ponteggi doing the fresco itself, he was overweight (he was said to be the spitting image of Silenus) and he suffered from asthma, as Mancini reports; we hear him speaking of the smaller paintings that he did, evidently for patrons at court. On the back of Agostino’s figure design for the group of Silenus in Chicago is a medallion with two cupids vying for a palm, who are evidently in the same hand as the Cupids in Frankfurt. The recto has also designs for the garland that must be by Agostino, together with the beginning of the idea of the boys climbing the arbor. The presence of the wrestling Cupids on the verso of the Chicago drawing referred to above demonstrates that Agostino must have had a hand in the invention of the contending figures of cupids, Eros and Anteros, in the Galleria itself, which for Bellori is the central theme of the whole decoration. And it is a reminder that there are a number of studies for subjects in the Galleria that look to be by Agostino, even when the painting itself turns out to be emphatically by his younger brother. While Agostino devoted himself in the final decade of his life, to original inventions that were essentially in competition with Annibale, he did, as we have read from Agucchi’s account- recognise that the latter was superior to him in this area, in which his rivalry had obviously proved challenging. The two panels either side of the Triumph of Bacchus must have been the last straw, for they challenged the monopoly of Annibale’s handiwork, and although the elder brother was much in favour with the cardinal’s entourage, he evidently wanted to be seen for his abilities in paint as well as invention.

A print whose subject epitomizes the theme of the Farnese Gallery is the 1599 Omnia vincit amor. Listed by Bellori among Agostino’s works, it has in modern times always been regarded as partly based on an invention of his younger brother, because the entwined nymphs on one side are evidently an echo of those painted in the Landscape with Diana and Callisto in the collection of the Duke of Sutherland, Mertoun. The picture is one of a pair, the other being the Toilet of Venus now in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Bologna: they were separated at the time of the Orleans sale in 1598, and have nearly always – in modern times – been seen as by different hands. It now seems that the figure group there is by Albani, who arrived in Rome after Agostino’s death, and to my mind the landscape is by his close friend and companion G B Viola, who contributed much to the Carraccesque landscape in early Seicento Rome (as will be argued in a forthcoming study). But there seems no reason to attribute the figures in Agostino’s print to his brother: Agostino had painted the subject of the print, Cupid subduing Pan, on the fireplace of Palazzo Magnani in Bologna, and the complete drawing in Frankfurt bears every indication of being entirely by his hand. The history of the paintings, however, demonstrates the force of the Annibale legend even in the next generation: both works were exported by the painter Jacques Stella to France, where their quality spoke for the myth of Carraccesque invention that was so persuasive for the generation of Cardinal Mazarin and Louis XIV, a narrative that was doubtless steered by Bellori himself who mentions the painting 31 as being in Paris with the Abbé de La Noue . But the same author also knew of Agostino’s erudition, he was l’autore delle sue invenzioni, le quali investigava con grandissima cura, and the nymph on the left of the Sutherland painting is evidently closely related not to any Annibale design, but to the left-hand nymph of the fresco in the Galleria of Glaucus and Scylla, (the traditional title of this scene) that no-one has ever associated with anyone other than Agostino. We do not know the source of the imagery for the Sapphic pair, but they have been to the same salon as the Three Graces in Agostino’s print (De Grazia, 1979, No. 183 p. 297) and the other courtesans that we see accepting gold and being beaten and penetrated by satyrs, felt up by cupids in the Lascivie, and there is no reason to think that this oil painting was designed or painted by Annibale. Looking at the Cupids on either side of the Frankfurt drawing, associated with the Farnese spinet now in the National Gallery, we can see that the landscape background there coincides with that of the Diana and Callisto, with the curved hillside in the distance and the trees in the intervening valley.

This also has that combination of observation from classical models (in the case of the drawing probably from cupids at either end of a Roman sarcophagus) with a landscape setting that has a well-staged perspective. Here Diana is having her sandal slipped off in precisely the same attitude as Venus undressed by Anchises in the Galleria, a painting where Agostino did the preparatory drawing (Christ Church, Oxford)32 . The figures are contained and obviously derived from the antique, and are reminiscent of the Niobids that were discovered in 1582 and set up as a tableau in the Villa Medici for Grandduke Ferdinando. This would be an important source for painters in the Seicento, most notably Poussin, and seems to be the origin of the compact classical physiognomies that Agostino and the Carracci school after him adopted… The Mertoun painting is an example of the sophistication of Agostino’s landscape style at the end of the Roman experience, one which was hugely important for his followers, notably Domenichino, who was the principal heir of this discipline, which combined a decorative idiom on a small scale with a history subject, a marriage that would have a great future in the Seicento. Unlike the canvases Annibale had done of landscape subjects in Bologna, which were probably part of larger architectural settings, this was a cabinet painting with a lot of classical allusions, doubtless obtained through exchanges with Fulvio Orsini, and one that also presented a framework of landscape perspective that could function as a stage for a narrative. This design was of great significance for the generation of patrons who wanted to use this agreeable landscape setting to act as a background for all sorts of involved stories and morality plays, and it is important to realize that this was part of the educational tools that Agostino’s inclination provided for the next generation. Because it relates so closely to the 1599 print, it is at the closing of Agostino’s career in Rome, and the fact that the companion had to be completed by other hands shows that it must have been one of the last pieces he did in Rome, probably for Odoardo Farnese himself. The idea that it has to be based on his brother’s invention is certainly due to the fact that most of Agostino’s prints are reproductive, whereas he had come to realise that he wanted be his own man well before he came down to Rome, and the exchanges he had with antiquarians like Fulvio Orsini gave him a range of subjects from the Antique that could be expressed in painting. Agostino’s etching is after all the central theme of the ceiling, and its date represents a crucial moment in the execution of the paintings of the Galleria, and although it is not necessary to assume that the decorations have a completely consistent narrative, this sex-laced innuendo had a lot to do with their success. It was after all what this overweight lecher was famous for, as we read his lines about the bella pargoletta che ancor non sente amore33 , and see from the erotic prints that had so much success. Bellori is something of a prude in explaining away some of the narrative he found in the sensualism present in sixteenth century fresco cycles, for although the world of Raphael and Italian mannerism was not as outrightly erotic as that of Rudolphine Prague, it needed some explaining away in the more reformist phase of the Seicento that he belonged to. The landscape detail, which is incredibly carefully described, is of key importance for the generation of Domenichino and Viola, and we should recall that on arrival in Rome they were both independent enough to stay on their own, so the teaching of Agostino was in fact more relevant than that of the already fading Annibale, who had left Bologna six years before. And Agostino evidently regarded landscape as part of quadratura, it is a new use of an essentially decorative idiom to make it the setting for history subjects. This is the more tightly controlled classicism that Agostino’s influence sought to impose, and as he grew to have more confidence in his inventive ability, he sought to impress it on the content of the scenes as well as their overall disposition.

There is no reason however now to regard Annibale as the inventor or painter of this greatpicture of Diana and Callisto that was always hugely admired, (and seen as the classical interpretation of Titian’s painting of the same subject, that was until recently in the same collection). But it has been falling out of favour in recent Annibale studies, viz Robertson and Benati34 ) and it should be recognised as the centrepiece of that compact classicism that Agostino developed in Rome, full of the organisation of landscape detail that his successors, Domenichino, Grimaldi and Poussin so appreciated. It takes the place that the celebrated Flight into Egypt has enjoyed in modern times, a work that is also a major landmark in the new classical’ landscape tradition, but done by Domenichino, as will be argued. The landscape tradition that comes from the Carracci in fact owes more to Agostino’s teaching models, and even though there are few examples of paintings (more as it happens than those securely given to his brother), his drawings show that he was a designer of compositions that could be readily varied and multiplied. The sophisticated range of devices in the Diana and Callisto come from a range of graphic and pictorial examples that were obviously familiar to the new generation of Bolognese painters in Rome, and actually constitute a much more important source of design than the master who stands for all the Carracci came to represent, who had a much looser approach to the genre. This after all was not just a pattern for the vignettes that pittori doratori did through the sixteenth century, punctuated with grotesques in decorative schemes, but it gave an articulated, naturalistic setting for some of the classical stories that had such attraction for the learned patronage that this revival of the antique had woken. The Mertoun painting is an example of the sophistication of Agostino’s landscape style at the end of the Roman experience, one which was hugely important for Domenichino, who was the principal heir of this discipline that combined a decorative idiom on a small scale with a history subject, a marriage that would have a great future in the Seicento. Unlike the canvases Annibale had done of landscape subjects in Bologna, which were probably part of larger architectural settings, this was a cabinet painting with a lot of classical allusions, and one that also presented a framework of landscape perspective that could function as a stage for a narrative. This design was of great significance for the generation of patrons who wanted to use this agreeable setting to act as a background for all sorts of involved stories and morality lessons, and it is important to realize that this was part of the range of educational tools that Agostino’s inclination provided for the next generation. Because it relates so closely to the 1599 print, it is at the closing of Agostino’s career in Rome, and the fact that the companion had to be completed by other hands shows that it must have been one of the last pieces he did in Rome, probably for Odoardo Farnese himself, or possibly for his brother and his future bride.

The drawings that can be even loosely associated with these landscape paintings are few, but in reality more than can be assembled in the cause of Annibale’s participation in the genre. A general consideration is that these studies are rarely connected with the features of painted landscapes, for it seems that this was an area where free composition was practiced. Despite Faberio’s praise for the drawing that the students at the Accademia degli Incamminati did ‘alla villa’, there seems little that actually reflects real features from the countryside, but the other side of this is that some of the handling is sufficiently personal to be recognised., and there is a more consistent thread in Agostino’s graphic output than in that of his brother, in this subject. It is likely that the majority of the latter were given that attribution as a result of the very brief accolades in the early biographies, following the same principle that applied to the paintings from the Carracci school. The absence of examples of Annibale landscape paintings from the Roman years did not discourage Bellori and other promoters of the Carracci from exporting pictures and drawings that were only generically Carraccesque, under Annibale’s name. Agostino was apparently quite diffident about his own painting, but he was paradoxically a much more articulate designer and teacher, using the graphic medium into order to distill his designs that are often much more finished, confident and organised. One of the first in Loisel’s catalogue, a drawing that belonged to Mariette with a nymph pointing (Inv. 7121, Loisel. No. 325 35) has figures that not only echo Diana’s gesture, but also the callipygian back of the righthand nymph in the Brussels Diana and Actaeon. The bucking goats are related to several other studies, including ones in Stockholm and Windsor, that show the artist trying persistently attempting to work out a profile for this element in the Farnese ceiling, just like the repeated side-saddle drawings connected with Europa in the little ex Farnese painting, and the Galatea in the Palazzo del Giardino fresco. Since the recognition that not only the painting of the Fete Champetre in Marseille, but also the drawing in the Louvre are by Agostino, it is easier to see his handwriting in the tree trunks, the same as we encounter in the Frankfurt drawing for Omnia vincit Amor, or the study in the Louvre for the Fete Champetre.

The Omnia vincit amor engraving is also very similar to the etching of the Fan, which nonetheless has been connected , for no very good reason, with the marriage festivities of Ferdinando de’ Medici and Cristina di Lorena in 1589. It is I think right to associate it with a festivity of this kind, and now we know that Agostino was still in Rome for the union of the Aldobrandini with the Farnese, as he engraved an epithelium on the occasion of the marriage in May 1600, it must be realistic to link this print with the ephemera of that celebration. The little landscape in the oval is close to that of the Omnia vincit amor, the backgrounds of the Lascivie (and that of the designs of the Tazza Farnese) and the two satyrs peeking at a bathing nymph are close to those of the Frankfurt preparatory drawing for the 1599 engraving. It turns out that the poetry whose first line is featured in the drawing for the fan (Private collection, England36) is from one of Michelangelo’s Madrigali – LXI, which begins Mentre i begli occhi giri, Donna… and continues with praise of the loved one ‘Che’n sì begli occhi io mi veggia sì brutto, / Tu ne’ miei brutti ti veggia sì bella’. Michelangelo’s poetry was not in fact published (by his nephew Lionardo) until 1623, but obviously these verses circulated among amateurs, and it is characteristic of Agostino to be so well-read. The head of Diana at the middle of the fan is a recollection of the Goddess in the Landscape with Diana and Callisto that must date from the same period, or indeed of the nymphs of the 1599 engraving. There are other landscapes that Agostino painted before he left Rome; perhaps it is no surprise that they did not survive with his name attached to them. Closely related to the Diana and Callisto is the Landscape with Silvia and the Satyr in the Bologna Pinacoteca37. Long admired as the work of Domenichino, its known history does not in fact go beyond the early nineteenth century. The carefully defined foliage on the left is a familiar foil to the distant view, with Silvia being pursued by a satyr into the distant planes: the group in the middle distance has her carted off as in the Louvre drawing (Inv 7456, Loisel No. 37038), where the principal motif is one of the girls as it were from from the Lascivie seen from behind, in a pose that is evidently based on the Hermaphroditus. Here is a satyr peeking round the tree to ogle Silvia, much like those in the medallion in the Fan, or those in the Lascivie. the structured perspective with little figures calibrating the distance. Agostino had engraved Bernardo Castello’s drawings for the 1590 edition of Tasso’s Gierusalemme Liberata, but the choice of such a literary source is unusual. The landscape details as well as the figures are closely related to those of the other pictures of this small group, and we have the same collection of hunting gear leaning against the tree on the left. The subject is from Tasso’s poem Aminta, set in the classical world at the time of Alexander the Great and first published in 1573, and Agostino uses similar devices to include the figure subject within the setting, with Silvia the nymph who inhabits this sylvain domain and is pursued and ultimately rescued and won by the shepherd Aminta, despite being dedicated to the chastity of the goddess Diana. The protagonists are very much in the front of the view, balanced on the left with the same props from hunting that are in the Diana and Callisto foreground and the same lively dogs – that are never quite as realistic as Annibale’s. They are variations on the theme of mythological nymphs that people the Galleria itself, and of course those of the Lascivie that must date from this period too. The trees and foliage are pretty idiosyncratic, and are matched by the character of Agostino’s drawings as we shall see. The graphic outlining of the tree on the left that frames the view is a coloured version of the foliage in some of the drawings, like another study from a mythological source, that of Salmacis and Hermaphroditus in the Louvre (Inv. 7492; Loisel No. 742)39.